E-mail: font@focusonnature.com

Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555

or 302/529-1876

|

PO

Box 9021, Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: font@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 or 302/529-1876 |

Updated

in February 2013

relating to a bird during the FOCUS

ON NATURE TOUR IN CHILE

in November/December 2009

What follows here was written and compiled by Armas Hill, the leader of FONT tours in Chile

During a ferry-boat

crossing (in the photo above) to Chiloe Island, on December 1, 2009, as part of the FONT Nov/Dec '09 Tour

in Chile, some storm-petrels were noticed that appeared different.

They had more white than would normally be seen on the Wilson's Storm Petrel,

thus appearing to have more contrast, with white upper wingbars, a seemingly

pale underwing, and even, most oddly, apparently white bellies.

What we did not know at the time was that earlier that same year, another group

of birders (from Ireland: Seamus Enright, Michael O'Keefe &

friends), in waters in much that same area, also observed

such similar

storm-petrels.

Since then, this news:

In February 2011, during a five-person multi-national expedition led by British

seabird expert Peter Harrison, 12 of the "mystery storm petrels" were

captured at sea near Puerto Montt, Chile. By so doing, that team has been able

to confirm the existence of a new species.

According to Harrison, "These birds appear to be a new species, as they are

so different from any other storm petrels we know." There are 22

known species of storm petrels worldwide.

The following narrative, from the blog "Birding Abroad", relates more

about the news:

Recent sightings of unidentified storm petrels in Seno Reloncavi, south

of Puerto Montt, Chile, have been confirmed as a new species, as recently

published in "Dutch Birding" (O'Keefe et al 2010).

A team of biologists led (as noted above) by British seabird expert Peter

Harrison, has just completed an expedition to that area of Chile.

The expedition followed Harrison's earlier examination of two skins of an

Oceanites

sp.

housed in the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales in Buenos Aires,

Argentina.

Those two skins had been described by Pearman as the first Argentine records

of the

Elliot's Storm Petrel,

Oceanites gracilis galapogoensis

(Pearman

2000).

On examining the specimens, Harrison concluded that the two originally collected

at El Bolson, Rio Negro province, Argentina, in February 1972 and November 1983

represented a hitherto undescribed taxon and were probably the mysterious

unidentified storm petrels of Puerto Montt, Chile, which is just 70 kilometers

west of El Bolson.

Two members of the team of biologists, Chris Gaskin and Karen Baird from New

Zealand, were both involved in at-sea captures and searches for the breeding

location of the recently rediscovered

New Zealand Storm

Petrel

(Gaskin

& Baird 2005, Stephenson et al. 2008).

The Chilean expedition spent 4 days at sea in the Seno Reloncavi area, where

they made use of chum or berley (fish scraps) to attract seabirds within range

of the specially designed net-guns. These were critical to the success of the

expedition and were developed in New Zealand for the capture of the

New

Zealand Storm Petrel.

Over the four days at sea, over 1,500 sightings of the new

Oceanites species

were recorded.

To enable the scientific description of the new species, the 12

birds (as noted above) were captured for the collection of biometric data

and samples of blood and feathers taken for genetic work.

The new species would appear to be most closely related to the

Elliot's Storm

Petrel, Oceanites gracilis. But in appearance it is intermediate between

the

Wilson's Storm Petrel and the

New Zealand Storm Petrel.

It shows a distinctive

pale upper wing crescent and a prominent white bar across the underwing coverts.

Unlike typical Elliot's Storm Petrels, the white feathering in the ventral area is

much more subdued and restricted and does not extend toward the upper breast. The

wing measurements are also very different and show no overlap with the mainland

Elliot's Storm Petrel.

The expedition team estimates a population of 5,000 to 10,000 birds in the Seno

Reloncavi area, where the new taxon appears to be the most abundant of the

resident seabirds, with flocks of several hundred individuals at chum slicks.

The timing of the expedition appears to have coincided with the fledging period

as juveniles were among the captured birds, suggesting that breeding occurs in

the Seno Reloncavi area, possibly beginning in November.

A wider search of the Seno Relanocavi and Golfo de Ancud area needs to be

undertaken in both summer and winter.

Further analysis of feather and blood samples is expected to confirm this

discovery and a full scientific publication is in preparation by the expedition

team.

That analysis has since been done, and in January

2013, the new species was described, the Pincoya

Storm Petrel, Oceaniites

pincoyae, published that month in "The

Auk", the publication of the AOU, the American

Ornithologists Union. A color illustration of the new storm petrel is on the

cover of that issue.

The name "Pincoya" commemorates a female water spirit in Chilote

mythology, a mixture of myths, legends, and beliefs of the people who live

on the island of Chiloe in southern Chile.

That mythology reflects the importance of the sea in the life of the

Chilotes (those who live on Chiloe Island).

Chilote mythology is based on a mixture of the indigenous religions of

the Chonos and Huiliches who have long been inhabitants on Chiloe, together with

legends and superstitions brought by the Spanish when they arrived there in

1567, thus beginning a fusion of elements that would form a separate mythology.

That Chilote mythology flourished, due to the isolation and remoteness of the

island culture from the more "mainstream" society of the Spanish and

other Europeans elsewhere in Chile,

In that mythology, the "Pincoya" is a female "water

spirit" of the Chilotan Seas. said to have long blond hair, and to be

of incomparable beauty, to be cheerful and sensual, and to rise from the depths

of the sea.

Naked and pure, she personifies the fertility of marine species. Through her

ritual dance she provides the residents of Chiloe with either an abundance or

deficiency of fish and seafood.

If she performs her dance facing the sea, it means that the shore will have an

abundance of fish.

When she dances facing the mountains, with her back to the sea, seafood will be

scarce.

Chilote mythology is appreciative of the "Pincoya" who is

believed to be good, beautiful, and humanitarian.

According to legend, Pincoya is the daughter of Millalobo, who was

the "king of the sea"' in Chilote mythology and a human named Huenchula.

Over the years, there have been a number of Focus On

Nature Tours to the island of Chiloe, where both the nature and the

culture have been enjoyed and appreciated.

On the island during those FONT tours, a wonderful assortment of birds

and mammals have been seen.

Birds have included colonies of penguins and other seabirds,

rafts of swans and other waterbirds, large flocks of godwits,

as well as parakeets, hummingbirds, tapaculos, and Magellanic

Woodpeckers and other birds of the fascinating Nothofogus forest.

Mammals have included the rare Marine Otter, or Chungungo,

and the diminutive deer called the Pudu.

Beneath the photos below is what was written in the FONT website in 2010, relating to the "Dutch Birding" article mentioned above.

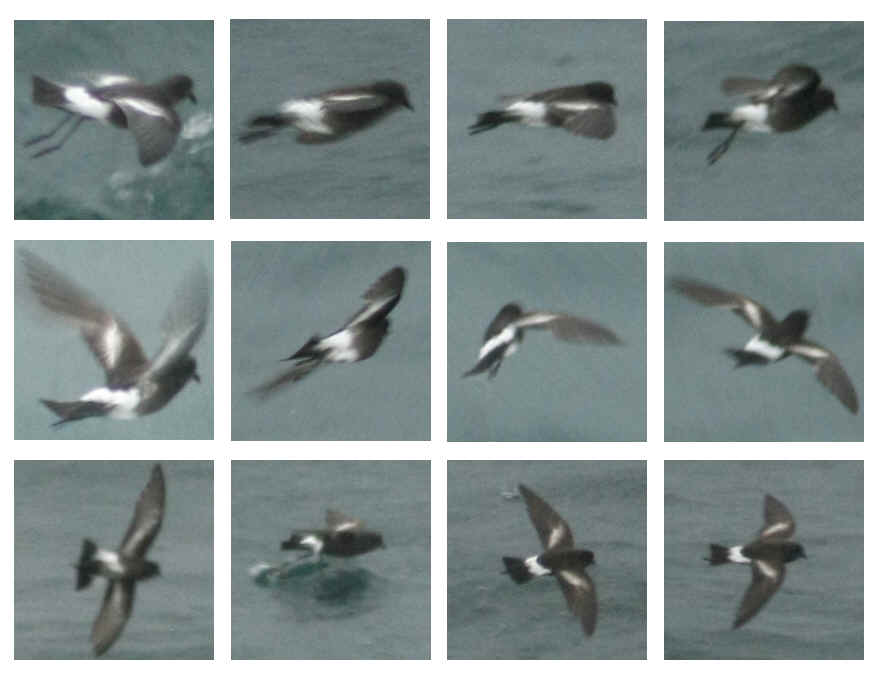

These photos were taken in nearly the same Chilean waters

a few months before our Nov/Dec '09 FONT tour,

taken in February 2009 by Michael O'Keeffe

This "mystery

storm-petrel" was seen during the FONT Chile tour

on December 1, 2009 from the ferry to Chiloe Island.

It has since been described, in January 2013,

as a new species,

the Pincoya Storm Petrel.

What

follows now, regarding these storm-petrels in southern Chilean waters, is from a

paper that was authored in 2009, by Jim Dowdall, Seamus Enright, Kieran

Fahy, Jeff Gilligan, Gerard Lillie, and Michael O'Keeffe, for DUTCH BIRDING

(published in 2010):

The most striking feature of the birds was the extent of white in the

plumage underneath, suggesting initially one of the

Fregetta

storm-petrels. However, other features seemed to rule out that option, including

the extent of dark on the flanks and the prominent carpal bar.

The birds appeared to have characteristics making them

Oceanites

storm-petrels, similar but perhaps slightly stockier of the

chilensis

Wilson's

Storm Petrel. But the whitish upper-wing and under-wing panels appeared more

striking than

chilensis.

The white on the rump appeared to wrap completely

around the vent/lower belly, although from photos it is hard to rule out the

presence of perhaps some dark feathering on the sides and the center of the

vent.

Below, some answers to a

couple questions that have been asked during the years, from 2009 to 2013:

Why have these birds apparently gone undocumented until now?

Other visiting birders, in recent years, in the coastal waters south of

Puerto Montt, and from the ferry crossing to/from Chiloe Island, have noted

similar birds.

For example, Peter Harrison first encountered them while working onboard the

tour vessel M.V. Linblad Explorer, out of Puerto Montt in 1983 and 1984.

Harrison also saw the birds again in later years. On two occasions, he remarked

that he "was lucky enough to have one land on the deck during the night and

was able to give them careful scrutiny. Using his only reference (Murphy, 1936),

and based on measurements he obtained, Harrison concluded the birds to be

chilensis.

The enigmatic chilensis race of the Wilson's Storm Petrel

has had a

checkered history.

Robert Cushman Murphy in the "Oceanic Birds of South

America" (1936) described how the taxa Oceanites

oceanicus chilensis

was inadvertently first published nomen nudum by W.B. Alexander in

"Birds of the Oceans" (1928).

The taxa was later described in detail by Murphy (1936) and referred to as the "Fuegian

Petrel", a new subspecies of the Wilson's Storm Petrel.

Subsequent to that, and for reasons not quite understood, the taxa was

"dropped" as a race of the Wilson's. Until very recently, only

two races of Wilson's Storm Petrels, oceanicus and exasperates,

were recognized in the literature, including by Harrison (1983, and in

subsequent editions).

Interestingly, in relation to the Wilson's Storm Petrel, Harrison has

noted that "Cape Horn birds have pale vents", again apparently

relating to chilensis, noting also some pale mottling on the lower belly.

Onley and Scofield (2007) have recently re-established chilensis as a

race of the Wilson's Storm Petrel.

So, a conclusion could be that the storm-petrels, with the white on their

vents/bellies in the Chilean waters south of Puerto Montt were undocumented in

part due to the lack of understanding of the form chilensis also

occurring in those waters, and probably most importantly, they were undocumented

because simply not many people were aware of

them.

The storm petrels, with the white apparently more extensive than chilensis,

have been observed south of Puerto Montt, in the channel north of Chiloe island (where

they were seen during the 2009 FONT tour), and also in the Gulf of Penas,

approximately 500 kilometers south of Puerto Montt. It is therefore suggested

that these birds are relatively localized and sedentary,

Could these birds really be a new species?

The most conservative explanation was that they would simply be a previously

un-described plumage or morph of one of the species already known from the

region.

The combination of plumage features of the new storm petrel perhaps most closely matches the Elliot's

Storm Petrel. But generally that species generally has much more white on

the upper belly and generally more dark feathering on the vent, creating a

distinctive divide between the white belly and the rump.

Also, the waters south of Puerto Montt seem surely to be too far removed, so far

south of the range of the Elliot's, which is a warm-water species, and

thus not apt to occur to cold southern Chilean waters.

Very interestingly in relation to the new storm petrel, repeating here

what has already been noted earlier:

in 2000 a note was published regarding two specimens of storm petrels

that were taken (back in 1972 & 1983) from El

Bolson, in the province of Rio Negro, in southern (Patagonian) Argentina.

They

were assigned to the northerly race of the Elliot's Storm Petrel, galapogoensis.

They erroneously represented the first (and the only) records of Elliot's Storm

Petrel for Argentina (where they would have been assumed to have been from the South

Atlantic.)

The wing measurements of the new "white-bellied" storm petrels from south

of Puerto Montt in Chile (now, the Pincoya Storm Petrel, Oceanites

pincoyae) indicate those birds to be larger than gracilis

Elliot's, and within the range of chilensis or galapogoensis (with

however, as already noted, their plumage features not matching either of those taxa).

The El Bolson (Argentina) birds are only marginally longer winged than the

Puerto Montt Oceanites pincoyae birds,

as studied by Harrison in the hand.

It has been determined that the two El Bolson specimens are examples of the

Oceanites pincoyae storm petrels of the waters

south of Puerto Montt, and not the Elliot's.

Returning again to the chilensis race of the Wilson's Storm Petrel,

some observers have been of the opinion that it may in actuality be closer to the Elliot's

than to the Wilson's.

With the new "white bellied" storm petrels (Oceanites

pincoyae) from south of Puerto Montt having now received analysis, it

may be worthwhile to re-think, and thus give further

study, the entire storm-petrel taxa in the region of southern Chile.

It is hard not to draw certain parallels between this story of storm petrels in

southern Chile and that of the New Zealand Storm Petrel, Oceanites

maorianus, that was only recently, in 2003, found to be alive and well.

Indeed, the "white-bellied" Puerto Montt/Chiloe Island birds, now

Oceanites pincoyae, share a

startling similarity with that rare species that lives on the far-opposite side

of the South Pacific Ocean.