E-mail: font@focusonnature.com

Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555

or 302/529-1876

|

PO

Box 9021, Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: font@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 or 302/529-1876 |

Rare Birds in Japan

noting those seen

during Focus On Nature Tours

A Summary compiled by Armas Hill

Codes:

(JPe): endemic to Japan

(JPeb): endemic Japanese breeder

Links:

Upcoming FONT Birding & Nature Tours:

in

Japan

in 2015

by geographic location

worldwide

Some Highlights from Past FONT Tours in Japan

In the FONT Archives:

Some Photos of People, Places, & More during FONT Japan Tours

A List & Photo Gallery of Japan Birds, in 2 Parts:

Part #1: Pheasants to Pittas

Part #2: Minivets to

Buntings

A List of Japanese Mammals (with some photos)

THERE HAVE BEEN 36 FONT BIRDING & NATURE TOURS IN JAPAN.

The following list & notes compiled & written by Armas Hill, who has led

FONT tour in Japan for about 20 years, and has himself birded in Japan for over

3 decades.

Classifications are those designated by Birdlife

International. The criteria for classifications follows the listing.

Japanese islands where the birds have been seen

during FONT tours are noted in

the listing below.

Species OF JAPANESE BIRDS

Classified as: CRITICALLY

THREATENED:

Baer's

Pochard Byran's

Shearwater Siberian Crane

Spoon-billed Sandpiper

Pryer's Woodpecker Amami Thrush

Classified as: ENDANGERED:

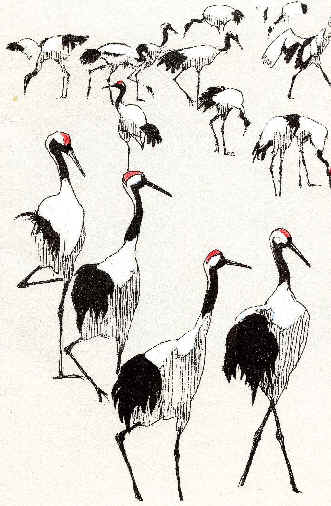

Oriental Stork Crested Ibis Black-faced Spoonbill Japanese Night Heron Red-crowned Crane

Okinawa

Rail Spotted Greenshank Blakiston's

Fish Owl "Owston's

(or

Amami) Woodpecker"

Classified

as: VULNERABLE:

Baikal Teal

Scaly-sided Merganser

Steller's Eider Long-tailed Duck

Short-tailed Albatross

Black-footed

Albatross Buller's Shearwater Chinese

Egret Steller's Sea

Eagle

Greater Spotted Eagle

White-naped

Crane Hooded Crane Swinhoe's Rail

Great Knot

Eastern Curlew Amami Woodcock

Saunder's

Gull Japanese Murrelet

Fairy Pitta

Amami Jay Izu Thrush Ijima's

Leaf Warbler Bonin White-eye

Marsh Grassbird

Yellow Bunting

Classified as: NEAR-THREATENED:

Copper

Pheasant Falcated Duck

Ferruginous Duck Laysan

Albatross Swinhoe's Storm

Petrel

White-tailed Eagle

Asian Dowitcher Long-billed Murrelet Black

Wood Pigeon

Ryukyu Green Pigeon Elegant Scops

Owl Japanese Waxwing Japanese Paradise Flycatcher

Japanese Reed Bunting

Some Species that have been classified as

NEAR-THREATENED:

Mandarin Duck Long-billed

Plover Grey-headed

Lapwing Ryukyu Robin

Silky Starling

Species in Japan classified as

CRITICALLY THREATENED:

1 BAER'S POCHARD

Aythya baeri

Honshu (during 1 FONT winter tour, in 1998)

The Baer's Pochard is a poorly known species has a small, declining population. Estimates

of the total population are

about 10,000 individuals. Most occur on mainland eastern Asia, breeding in

southeastern Siberia and northeastern China, and wintering in China, Korea,

Myanmar (has been known as Burma), and eastern India.

2 BYRAN'S SHEARWATER

Puffinus bryani

The Byran's Shearwater was described in 2011, from a specimen that had been

collected in 1963 on Midway Atoll, northwest of Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean.

At that time, that small shearwater was thought to be a Little Shearwater.

Later, a second specimen was tagged and recorded on Midway in 1990.

In February of 2012, DNA tests on 6 specimens of Puffinus bryani found in the

Ogasawara Islands of Japan, alive and dead between 1997 and 2011, determined the

birds to be Bryan's Shearwaters. It is assumed that the species still

survives in the uninhabited Japanese Ogasawara Islands.

Another shearwater in the Ogasawara Islands is

not well known. It was considered as part of the Audubon's Shearwater.

It is now named the Bannerman's Shearwater,

and it is a Japanese endemic breeder only in the Ogasawara group of islands.

Some have recently referred to it by the name "Tropical

Shearwater".

3 SIBERIAN CRANE

Grus leucogeranus

Kyushu (during FONT winter

tours in 1997, 2000, 2001,& 2004)

The Siberian

Crane is a rarity in Japan. On occasion (as during the 4 years noted

above), a single individual winters at Arasaki, on the southern Japanese island

of Kyushu, with the combined approximately 10,000 Hooded & White-naped

Cranes.

The Siberian Crane is now classified as "critical" because it is

expected to undergo an extremely rapid decline in the near future, primarily as

a result of the destruction and degradation of wetlands in the areas of its

migration and wintering grounds. The wintering site, holding 95% of the

population, in China, is threatened by changes that will come about with the

Three Gorges Dam project.

The total population of the species is between 2,500 & 3,000, making it, at

this time, the 3rd rarest crane in the world.

The Siberian Crane is a large, white bird with black on its wings, is (as noted above), at this

time, the third rarest crane in the world (after the Whooping and the

Red-crowned Cranes).

It is probably, at this time, the most threatened of the world's cranes.

Until just over 20 years ago, in 1981, the Siberian Crane was believed to be

even more rare, and endangered. It was in that year that about 800 birds were

discovered to be wintering at Lake Poyan, China's largest freshwater lake, along

the Yangtze River. With that, the known population nearly doubled. Subsequent

field surveys showed the total population of the species to be from 2,500 to

3,000 birds.

Still the outlook for the species is precarious. According to the crane

specialist, George Archibald, "from the tundra to the subtropics, few

endangered species involve so many complex problems in so many countries as does

the Siberian Crane".

There are 3 populations of Siberian Cranes. All but a few of the maybe 3,000

birds belong to the eastern population, which breeds in northeastern Siberia,

and winters along the Yangtze River in China.

Another very small central population breeds in the lower basin of the Kunovat

River in western Siberia, and winters in the Indian state of Rajaasthan (most

regularly in the Keoladeo National Park). When this population was observed at

its wintering grounds in 1992-93, it included just 5 birds. Only 4 birds were

observed at the Kunovat breeding grounds in 1995.

The western population (also very small and threatened), which apparently held at 8 to 14 birds in the late 1980's and early 1990's, has wintered at a single site along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea in Iran. The exact location of the breeding grounds of that population is unknown, but it's thought to be in the extreme northern portion of European Russia.

Thus, 2 populations of this species are extremely vulnerable (on the verge of extinction). These populations have continually declined from just over 100 birds in the 1960's (when they were discovered).

The Siberian Cranes that have occurred in Japan as vagrants have been

wanderers, on occasion, from the larger eastern population of the species that

normally winters in China.

Actually, in the past, the Siberian Crane was a common winter visitor in Japan

on Kyushu prior to the Mejii Era. Throughout the 20th Century, it became an

accidental, but there were some occurrences from Hokkaido south to Okinawa. Most

in Japan, however, continued to be on Kyushu. Interestingly, there were single

birds in Hokkaido in Oct-Dec 1977 and May-Sep 1985. The latter was a summering

bird in the Kushiro district, where the resident Japanese population of

Red-crowned Cranes reside.

Where Siberian Cranes breed, huge distances separate nesting pairs. Within each 1000 square kilometers in the breeding range, there are only 1 or 2 pairs of cranes.

The Siberian is the most aquatic of all cranes, exclusively using wetlands for nesting, feeding, and roosting. The nests are in bogs and marshes. In migration and in wintering areas, the bird prefers to feed and roost in shallow wetlands. Preferred foods are roots, sprouts, and stems of sedges and other aquatic plants. It seldom forages above the water line.

Two more photos of the

Siberian Crane in Japan.

The species is truly an exciting rarity to see in Japan.

During FONT tours there, we've seen it 4 different years,

but never more than a single bird.

In the lower photo here, a Siberian Crane (left)

is in a field with a White-naped Crane (right).

4 SPOON-BILLED SANDPIPER

Eurynorhynchus pygmeus

Amami (during

1 FONT winter tour)

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was seen during one

FONT Winter Japan Tour on the southern Japanese island of Amami.

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is an

overall very rare species, breeding in far eastern Siberia. It winters coastally

in Southeast Asia.

The global population of the species was, not long ago, in the early 2000s, estimated as under 4,000

birds. The population at the known breeding grounds was said to be

about 1,000 individuals, thus indicating a greater than 50 per recent reduction

in the last decade or so.

Not only is the global population of the species declining rapidly, there is

another problem: in that population, recently, there has been very little

recruitment of young birds.

Although breeding success is low, it seems that the main factor in the

Spoon-billed Sandpiper's decline appears to be the low rate of return to the

breeding grounds.

Data collected from 2003 to 2009 on birds at Meinypilgyno (the main breeding

site for the species in far-eastern, Siberian Russia), it is suggested that

recruitment into the adult breeding population was effectively zero in

all those years (2003 to 2009), except for 2005 & 2007.

When we first started at FONT to note the classification of the Spoon-billed

Sandpiper in the 1990s it was listed as "vulnerable".

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was uplisted to the category of "critically

endangered" in 2008, when the total breeding population of the species

was thought to be from 150 to 320 pairs.

In 2009-2010, the estimate was sadly revised downward to from 120 to 200

pairs.

One factor that may be responsible for the decline of the Spoon-billed

Sandpiper has been the loss of resting and feeding areas along the migration

flyway for the bird. There are about 8,000 kilometers of coastline between the

bird's breeding grounds in Arctic Russia and its non-breeding grounds in

southeast Asia. That's a long distance traveled by the bird that's about 6

inches in length.

The particular site along the coast in South Korea where the largest-ever

concentration of migrating Spoon-billed Sandpipers was recorded is now

the site of the world's biggest reclamation project. That habitat, vital for

bird, has been lost.

Other tidal mudflats around the coast of the Yellow Sea are rapidly being lost

to agriculture, industry, and urban development.

Another factor in the bird's decline is that at its wintering grounds in Myanmar

(Burma) and Bangladesh, numbers of them have fallen victim to the trapping of

sandpipers by hunters.

And when a population is as small as it for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper,

any number lost by such practice is detrimental.

Starting in 2008, an international team of researchers has surveyed, each year

in January, in Myanmar the Arakan coast and that of the Gulf of Martaban, the

wintering population of Spoon-billed Sandpipers.

The coast of the Gulf of Martaban has become known as the most important

wintering site for the species with about 220 birds found in 2010/2011.

Based on data from the breeding grounds, that is about half the estimated world

population, and over twice as many birds as found at all the other known

wintering sites put together.

Although the trapping by local hunters in Myanmar, referred to above, does not

deliberately target Spoon-billed Sandpipers, they are caught as a "bycatch"

in nets set for larger birds or pegged close to the mud to catch retreating fish

as the tide goes out.

The 2010 survey confirmed this large-scale hunting and trapping along the

Gulf of Martaban. Hunters indicated trapping up to 350 waders (or shorebirds) in

a single night.

One morning in January 2010, a hunter brought the survey team a Spoon-billed

Sandpiper he had caught the previous night along with about 100 Red-necked

Stints.

The single Spoon-billed Sandpiper, still alive, was marked with a red

flag and released by a group of local children.

That same hunter also indicated that he had last caught a Spoon-billed

Sandpiper the previous August (in 2009). It was an immature bird.

Not only are young birds more likely than adults to fall victim to hunters, they

are also likely to be affected disproportionately because they are thought not

to return to the breeding grounds until they are two years old. Some, during

that time, are speculated to spend the entire intervening year in their

non-breeding

area.

In September 2012, at a global meeting in Korea of biologists and other

environmental scientists, a list was distributed of the "100 Most

Endangered Species in the World", referring to all life, animal and plant.

It was under the auspices of the International Union for Conservation of Nature,

and the Zoological Society of London.

In that list, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper was positioned as number #10, making it

the "most endangered bird species on Earth" in the opinion of that

group, and sadly a candidate, unless something is done, for extinction.

For more about the 100 Species in the List, go to: ENDANGERED

SPECIES

Above:

a Spoon-billed Sandpiper in breeding plumage.

Below: In non-breeding plumage, a Spoon-billed

Sandpiper

appearing as one was in Amami, Japan during a FONT tour.

In 2012, the conservation group SOS,

"Save Our Species" was a partner in an innovative

project to boost the number of juvenile Spoon-billed Sandpipers at their

breeding grounds in Chukotka, in eastern Russia.

With the WWT, the "Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust", a IUCN

member working with the Moscow Zoo and "Birds Russia",

there was tremendous success, during the summer of that year, hatching, rearing,

and releasing 9 Spoon-billed Sandpiper chicks.

Those 9 chicks were hatched from 11 eggs carefully taken from the breeding

grounds on the tundra. They were monitored, hatched, and nourished in the nearby

village of Meinypil'gyno before being released. The project required constant

attention and effort. The fledglings gained strength living in an open-air

aviary designed to shelter the birds from predators. For added protection, a

guard kept vigil day and night.

The pioneering work is significant in that in the wild just 3 Spoon-billed

Sandpipers out of every 20 eggs survive long enough to start their 8,000

kilometer migration to southeast Asia.

Also, as part of the project, another 20

thumbnail-sixed eggs were transported from Arctic Russia to a WWT facility in

Slimbridge, England.

The first chicks were hatched there on July 4, 2012.

Of the 20 eggs that were brought to the UK, 18 chicks successfully hatched.

Those new birds were added to 12 fully-grown Spoon-billed Sandpipers that were

already at the WWT center, having been brought in at the start of the

conservation breeding program in November 2011.

The eggs, that were brought to England in 2012, were for more than 17 hours in

flight, transported by helicopter and airplane in a journey that took, totally,

7 days to complete.

One of the eggs cracked during an airport inspection and had to be sealed using

nail varnish.

When the Spoon-billed Sandpiper chicks hatched, they were about the size of a

large bumblebee.

The WWT hopes that the increasing size of the captive flock of Spoon-billed

Sandpipers in the UK would help trigger breeding behavior in the birds when they

would later reach maturity at two years of age.

A

Spoon-billed

Sandpiper illustrated in England,

in the early 20th Century,

about a hundred years

before a conservation project in the UK

aiming to save the species.

5 PRYER'S

WOODPECKER (also called OKINAWA

WOODPECKER) (JPe)

Dendrocopos (formerly Sapheopipo)

noguchii

Okinawa (during FONT spring, summer & winter tours)

The Pryer's, or Okinawa Woodpecker was considered close to extinction in the 1930's.

Population estimates since

1950 have ranged from 40 to 200 birds, with the most recent estimate being of 90

birds.

This species has been found during every FONT tour in Okinawa.

The Pryer's, or Okinawa

Woodpecker

The Yambaru forest

(above) in northern Okinawa is the only place on Earth for the

Pryer's, or Okinawa Woodpecker and the Okinawa Rail (referred to later in

this list).

Both species have been found there during FONT Japan Tours

along with some other notable birds including the Amami Woodcock (also in

this list),

and other rare wildlife such as the Okinawa Spiny Rat and the Okinawa Flying

Fox.

The Okinawa forest, in the photo

above, known as "Yambaru" has been visited during over a dozen FONT

tours over the years.

A number of rare & special species live in that region. Most notable

among the birds are the very rare Pryer's Woodpecker and the Okinawa

Rail.

We've spent many hours, during our tours, both in the day and after dark,

exploring that forest. At night, in that forested area we were in the quest of

the rail, owls, and the Amami Woodcock that occurs in northern Okinawa in

addition to the more-northerly island of Amami.

A very rare mammal we've seen there during FONT tours, on one

occasion was the Okinawa Spiny Rat (in the list referred to previously,

with the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, of the "100 Most

Endangered Species in the World").

Another rare animal we've seen there is the Okinawa Flying Fox, Pteropus

loochoensis, a "megabat" in the Pteropodidae family.

It was previously listed as "extinct" by the IUCN, but because

the two known specimens are taxonomically uncertain and of "unknown

provenance", it was changed to "data deficient".

Our two sightings of the Okinawa Flying Fox were both very late in the

day, as it was getting dark.

Some taxonomists treat the Okinawa Flying Fox, Pteropus loochoensis,

as a subspecies of Pteropus mariannus, the Mariana Fruit Bat, with

a range on Pacific islands from the Japanese Ryukyu islands in the north, south

to Guam.

6 AMAMI

THRUSH (JPe)

Zoothera major

Amami

(during FONT spring,

summer & winter

tours)

In the mid-1990's, the breeding population of the Amami Thrush was estimated as being about

60 birds. The similar White's Thrush is smaller.

The Amami Thrush has a cheerful

song, delivered mostly in the morning, and similar to that of the Siberian

Thrush, another Zoothera species. The White's Thrush has a more mournful song

delivered mostly at night.

The Amami Thrush, found only on that island, is

confined to mature (over 60 years old), subtropical, evergreen forest, at an

altitude of 100 to 400 meters. It is a shy bird.

Species in Japan classified as

ENDANGERED:

7 ORIENTAL

STORK

Ciconia boyciana

Kyushu

(during 2 FONT winter

tours, very rare on Kyushu)

With a total population of about 2,500 birds, the Oriental Stork breeds only in

the Amur and Ussuri basins (along the border of Siberia and China), and winters,

mainly, in eastern & southern China.

The last Oriental Stork

of the breeding population that was in Japan died back in 1971. That was on the

main Japanese island of Honshu, near Kinosaki.

A few years before nesting Oriental Storks

were extirpated in Japan, a re-introduction program began, with some birds from

Russia.

In May 2007, for the first time since 1964, an Oriental Stork chick

successfully hatched in Japan. That was in that same area of Honshu, near

Kinosaki, where Oriental Storks previously

were.

Since then (in 2011), about 50 Oriental Storks

were living in the wild in wetlands and fields in that area.

A key part of the successful return of the Oriental Stork

in that area is that a program was initiated with local farmers for the growing

of rice without pesticides. Thus, the food of the storks, fish and frogs, have

again flourished, as have the storks and other birds too.

For an itinerary of an upcoming FONT tour to the place in Japan with Oriental

Storks, and without pesticides, go to:

A JAPAN TOUR IN THE SPRING FOR SOME SPECIAL BIRDS

8 CRESTED IBIS

Nipponia nippon

Late one afternoon, during the May 2010 FONT tour, near the city of Kanazawa, on Honshu, we went to a museum to see what was to be a most interesting exhibit about a bird, known in Japanese as the "Toki". Its English name is the Crested Ibis. Its scientific name is Nipponia nippon. "Nippon" means "Japan".

The Crested Ibis is one of the rarest of the world's birds. A few decades ago it seriously flirted with extinction.

When I began birding in

Japan in the early 1980s, my bird book, and nearly the only one available in

English, was "A Field Guide to the Birds of Japan" published by the

Wild Bird Society of Japan, with its second and last printing in English in

1983.

On the cover of that book was a color illustration of two Tokis,

or Japanese Crested Ibises, in

flight. I've never forgotten that cover illustration! And, yes, I have hoped to

somehow one day to see the bird!

Crested Ibis

In the text of that

"Field Guide to the Birds of Japan", regarding the Japanese

Crested Ibis (as it was called then), it was

stated:

"In 1981 all 5 wild birds (remaining in Japan) were captured on Sado

Island for cage breeding. In 1982, 1 male and 3 females were still alive in

cages on Sado. In 1981, 7 (wild) birds were found in (a remote part of central)

China." (Those 7 birds in China were 4 adults and 3 chicks.)

The last of the Crested Ibises born out of captivity in Japan died in

2003.

At the Crested

Ibis exhibit we visited in the Kanazawa museum, there

was a map on the wall showing what had been the distribution of the bird in

Japan. It struck me as quite interesting that historically a center of abundance

had been the picturesque Noto Peninsula where we had birded the previous day.

The birds, when there, favored rice paddies where they fed on frogs.

If, by some quirk, we had seen a Crested Ibis,

an ultimate rarity, when there, it would have made our rare Chinese Egret

that we had seen a few years previously in a rice field, "abundant" by

comparison!

Sado Island, by the way, the last home of the Japanese Crested Ibis

in Japan, is not far, really, as a bird would fly, from

the north end of the Noto Peninsula where we visited a lighthouse.

Also on the wall in the Kanazwa museum, there was a series of photographs, all taken about 3 to 4 weeks before our visit. In one of the photos, there was a baby Crested Ibis that had just been born in captivity.

In a newspaper, just before we left Japan, there was the not-so-good news that Crested Ibises that had been released into the wild on Sado Island, had, once again in 2010, failed to breed. Four pairs had laid eggs there in the spring of 2010. Ultimately, all of the nests were abandoned. Disturbance by crows seemed to be a significant factor. If the Crested Ibises on Sado had bred, it would have been the first successful breeding in the wild of that species in Japan in 34 years.

Some good news, however, is

that the population of Crested Ibises in China

has been steadily increasing. For the past 23 years, since when only 7

individuals were found, China has bred and protected the species.

By June 2002, the wild population in China numbered 140 birds, and the captive

population there in 2 breeding centers was about 130 birds.

The most recent population estimate in China is of about 500 individuals.

In Japan, the Crested Ibis historically, in the early 19th Century, was common and widespread. In the late 19th Century and through much of the 20th Century, it declined drastically.

As recently as the mid-20th Century, there were two wild populations of Crested Ibises on the Noto Peninsula. One group there, in 1957, consisted of 14 birds. By 1961, it was down to 3. It nested there for the last time in 1962. In 1964, a single bird remained, which was later to be moved to captivity on Sado Island in 1969.

On Sado Island, there were 27 wild Crested Ibises in 1941. The following decade, in 1957, there were only 11. The decline there continued until, as noted, the species became extinct in the wild in Japan in 1981.

Since 1985, Crested

Ibises from China have been transferred to Japan for

captive breeding.

Over 100 individuals are now in captivity, with some in zoos, and about 30 (that

is 29) at the Japanese Crested Ibis Preservation Center on Sado Island.

In September 2008, that center released 10 of the birds as part of its Crested

Ibis restoration program, which aims to have 60 ibises in the wild by 2015.

Hopefully, toward that end, the breeding success in Japan will improve, so there

would be a growing Japanese population as there has been in China.

An update:

In the spring of 2012, the first Crested Ibises

were born in the wild in Japan since 1976.

The first chick was seen in the camera (at the

nest) on April 22. It was the first of 3 chicks in the nest.

The parents were a 3 year-old male and a 2 year-old female. Both were released

from captivity in March 2011, among about 45 released Crested Ibises

known to be alive at that time (in the spring of 2012).

As of 2012, 78 Crested Ibises have been

released into the wild on Sado Island since September 2008.

9 BLACK-FACED SPOONBILL

Platalea minor

Honshu (during 1 FONT winter tour)

Kyushu (during FONT winter tours)

Amami (during 1 FONT winter tour)

Okinawa (during FONT winter tours)

The global population of the Black-faced Spoonbill is estimated as being about only 700 birds. It

breeds on small islands off the west coast of Korea, and in one province of

eastern China. It winters from southern Japan south to Taiwan, Hong Kong

(China), and Vietnam.

10 JAPANESE NIGHT HERON

Gorsachius goisagi

11 RED-CROWNED

CRANE

Grus japonensis

Hokkaido ("Japanese Crane")

(during all FONT spring & winter tours on Hokkaido)

Kyushu

("Manchurian Crane")

(during 1 FONT winter tour, very rare on Kyushu)

The Red-crowned Crane is the 2nd rarest crane in the world, after the

Whooping Crane in North America.

The total Red-crowned Crane population in the wild has recently been estimated as

being from 1,700 & 2,000 birds.

As of 2011, the estimate of the global population of Red-crowned Cranes

was 2,750 individuals in the wild, but with only 1,650 of them being mature

birds.

In Japan, there is a resident population (information follows).

In mainland Asia, there is a migratory population that breeds in

northeast China and southeast Russia, and winters in Korea and China.

Recent numbers of wintering birds, in the mainland Asia population, have been:

600 to 800 in China

300 to 600 in North Korea (that number has been increasing)

200 to 300 in South Korea

Also notable in mainland Asia is that the first Red-crowned Crane ever

found in Mongolia occurred there in 2003.

In Japan, the current resident population of the Red-crowned Crane

is on the northern island of Hokkaido, and there only in the

southeast portion of that island. It occurred also in southwestern Hokkaido

until about a hundred years ago.

But now, southeast Hokkaido is the only place in Japan where the

Red-crowned Crane normally occurs.

At one time, it bred on all 4 of the main Japanese

islands, but it declined dramatically in Japan in the 19th Century. By 1890, it

remained in Japan only in Hokkaido.

A Red-crowned Crane in northern Honshu in June 2008 was the first

sighted on that island in a hundred years.

In the 1920's, the total Japanese population of the Red-crowned Crane was only about 20 individuals.

Since then, the number in Hokkaido, due to protection and artificial feeding (in

the winter), has increased, as noted below, to over 1,000 birds.

At the time of the first FONT tour in Japan, in 1993, there were 569 resident

Red-crowned Cranes in Japan on Hokkaido.

Just over a decade earlier

(when Armas

Hill made his first visit to Hokkaido to see Japanese, or

Red-crowned, Cranes), there were just over 300.

The following list shows how the population has changed

(increased) in Japan since then.

THE POPULATION OF RED-CROWNED CRANES IN HOKKAIDO DURING THE LAST 3 DECADES:

1980 - 251

1981 - 277

1982 - 309

1983 - 333

1984 - 339

1985 - 383

1986 - 421

1987 - 390

1988 - 416

1989 - 463

1990 - 453

1991 - 505

1992 - 522

1993 - 569

1994 - number not available

1995 - 600

1996 - 619

1997 - 615

1998 - 706

1999 - 740

2000 - 771

2001 - 887

2002 - 898

2003 - 948

2004 - 1,003

2005 - 1,081

2006 - 1,013

2007 - 1,200

2008 - 1,280

2009 - 1,324

2010 - 1,235

2011 - 1,143

2012 - 1,163

As noted above, there is a migratory population of the Red-crowned Crane on continental Asia in northeast China, eastern Siberia, and

Mongolia, wintering in

eastern China and Korea. In 2004, that population was determined to be

between 1400 and 1600 birds.

One of these

Red-crowned Cranes (a

"Manchurian Crane", rather than a

"Japanese Crane"), an immature bird, was seen on Kyushu (with

White-naped

Cranes &

Hooded Cranes) during the FONT February 2005 tour. It was the first such

occurrence of a Red-crowned Crane there in 37 years!

Years ago in Japan, a tradition developed with the folding of 1,000 paper

cranes. Doing so, a person petitioned "a crane" for happiness,

good luck, and a long healthy life. Strings of paper cranes were often hung at

temples and shrines.

In 2011, students around the world folded paper cranes to help raise

money for earthquake and tsunami victims in Japan.

Link to: MORE PHOTOS OF CRANES DURING FONT TOURS IN JAPAN

12 OKINAWA RAIL (JPe)

Gallirallus okinawae

Okinawa (during FONT spring & winter tours)

13 SPOTTED

(or

NORDMANN'S)

GREENSHANK

Tringa guttifer

The Spotted, or Nordmann's Greenshank is very rare, breeding only

by the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, and on North Sakkalin Island (north of

Japan) and possibly in the western Kamchatka Peninsula. In Japan, it is a rare

migrant.

14 BLAKISTON'S

FISH OWL

Bubo

(formerly

Ketupa)

b. blakistoni

Hokkaido (where it has been

seen during every FONT late-fall & winter tour; there have been 24 such tours)

This large and very rare Blakiston's Fish Owl occurs in southeastern Siberia (where there

may be a few hundred birds), China (where there may be up to a hundred birds),

and in central & eastern Hokkaido in Japan (where there's an estimated 120

birds). Its total population may thus be only in the hundreds, less than a

thousand birds.

Blakiston's Fish-Owl, Hokkaido, Japan

This bird is as extraordinary and formidable as any owl in the world. The

Blakiston's Fish Owl (as it has traditionally been called) is huge, with a

wingspan of about 6 and a half feet. It's larger than the Eagle Owl of Siberia.

Its legs are fully feathered. Its toes are bristly as are those of other fish

owls. It's interesting that structurally the Blakiston's Fish Owl has features

of both the "fish owls" (genus Ketupa) and the "eagle owls"

(genus Bubo).

In addition to Hokkaido, Japan, the species occurs only in far-eastern Siberia

(including Sakhalin and the southern Kurile Islands) and adjacent Manchuria, In

that area of mainland Asia, with a cold climate and severe winters, there may be

a few hundred birds. They inhabit dense, dark, primeval forests, either

coniferous, deciduous, or mixed, bordering lakes, rivers, and even the ocean

shore. They live in cold and difficult places for birds that eat mostly fish.

On the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido (a place where winters can

also be severe), Blakiston's Fish Owls are seriously endangered, confined to

relict areas of undisturbed forest. In 1983, less than 30 birds were recorded.

The following year, as survey workers gained more confidence of those guarding

secret locations, some 50 birds were located. During that year, 1984, however,

only 2 pairs were known to have bred successfully. Since then, in Hokkaido, with

successful nest box schemes in the forest, there has been some improvement in

nesting productivity. In the wild, nests are usually in large, hollow tress high

above the forest floor, but sometimes in decayed fallen trees closer to the

ground.

In the Siberian portion of the bird's range, Blakiston's Fish Owls have been

found at a density of 1 pair to every 7.5 to 9 miles of large river. In

Hokkaido, in all of the river valleys now occupied by owls, that figure is

less than 6 miles. Territories are occupied by birds for years. Individual owls

are so attached to their territories that a bird which loses its mate will

remain alone until another may arrive by chance.

Blakiston's Fish Owls are active throughout the night, as well as around dusk

and dawn. In the summer, they may do some hunting (to feed their young), during

lighter hours of the long summer days. In the winter, they're exclusively

nocturnal, emerging after sunset.

The territorial song is deep and resonant (although it does not travel as far as

that of the Eagle Owl). Males and females call together in duets.

Blakiston's Fish Owls, aptly, prefer fish as their primary food. In the late

summer, they feed on trout. In the autumn, they turn to salmon. Also, at times,

they eat: pike, catfish, burbot, and crayfish. In the spring, they live largely

on swarms of frogs that spawn in riverside marshes. Small mammals (such as hares

and martens) are also eaten, as well as an occasional duck, Hazel Hen, or

smaller bird. At some places, the owls feed along rocky seacoasts. Where they

exist in sufficient numbers (and that's not many places), they may gather during

the winter in small groups by openings in the river ice.

In Hokkaido, Japan, the Blakiston's Fish Owl, like the Brown Bear, was once held

in reverence. The fish-owl was known as "the god who defends the

village". Later, it suffered persecution, especially during the winter when

it was compelled to live close to openings in the ice, and, therefore, could

more easily be killed.

Today, under Japan's conservation laws, the Blakiston's Fish Owl is fully

protected.

Recently, the fish-owl in Japan is said to have suffered, ironically, from the

attention given to it by people who actually favor its protection and

well-being. This applies particularly to photographers (and there are many of

them in Japan) and other enthusiasts. There are some who don't realize the

damage they can cause the bird. Recent efforts to discourage them have included

trapping the owls and placing highly-reflective rings on their legs to make them

less attractive in flashlit photographs. It's become a matter of concern to

ornithologists that such "extreme methods" seem needed in order to

protect a bird that's on the verge of extinction in

Japan.

Above & below: the Blakiston's Fish Owl

photographed in Hokkaido, Japan.

15 "OWSTON'S

(or

AMAMI)

WOODPECKER" (JPe)

Dendrocopos (formerly Picoides) (leucotos) owstoni

Amami (FONT

spring & winter

tours)

Endemic to Amami Island, the "Owston's Woodpecker" has traditionally been considered a

subspecies of the White-backed Woodpecker, as the largest and darkest race of

that wide-ranging species that occurs across the Palearctic. So distinctive is

this Amami resident, however, it may well be determined to be a full species.

Species in Japan classified as

VULNERABLE:

16 BAIKAL TEAL

Anas formosa

Honshu (during FONT winter tours)

Kyushu (during

FONT winter tours)

During the years of many of the FONT tours in

Japan, the Baikal Teal was classified by Birdlife International as

"vulnerable".

However, more recently, that organization has changed the classification of the

bird to that of a species of "least concern", as its population has

been increasing.

However, in this listing, we're keeping the species in this position as its

story is so interesting, and the status of the bird may yet change

again.

In the first decade of the 21st Century, the population of the Baikal

Teal has grown rapidly, and the species has not experienced the decline that

was predicted. That notwithstanding, the species remains potentially threatened

by a number of factors. it tends to congregate in very large flocks, and it

suffered rapid declines in many parts of its range in the 20th Century, due to

various threats.

At roost sites, with a large number of birds, significant numbers have died

recently during disease outbreaks, Also, dry rice paddies, that have been

favored feeding sites, have been converted to vegetable farms and other uses.

If evidence arises that such threats cause a decline, the Baikal Teal may

warrant uplisting.

The Baikal Teal h was classified at the end of the 20th century as "vulnerable"

as it had, for years, a rapidly declining population.

In the

early 20th Century, it was one of the most numerous ducks in eastern Asia, with flocks of several thousand

regularly reported. During the 1970's, and afterwards, there was a significant decline.

At least in part, that decline was thought to be due to excessive shooting or

netting in the bird's wintering range and along its migration routes.

The bird

has had a habit of gathering in large dense flocks, and making predictable daily

movements. There's an account of about 50,000 birds being netted during 20 days

by 3 hunters in Japan in 1947.

In South Korea, in the early 1990's, there were, at 2 locations, about 20,000

and 30,000 birds.

In Japan, during the last 50 years of the 20th Century, and into the 21st

Century, the Baikal Teal decreased from a status

of "abundant" in the winter to that of being "uncommon".

As the 21st Century began, wintering counts of the Baikal Teal in South

Korea increased dramatically, from about 20,000 birds (as noted in the early

1990s) to a total of 658,000 recorded during surveys in 2004, including 600,000

along the lower Geum River.

A very large number of 1.06 million birds was counted in January 2009, with

concentrations of over 20,000 birds at 6 different sites.

Thus, there has been a genuine population increase in South Korea, with a yearly

average increasing from 11,533 birds during the period 1999 to 2003 to 314,994

birds from 2005 to 2009.

This increase in the South Korean wintering population of the Baikal Teal

is thought by some to be linked an increase in newly reclaimed land and a

decline in hunting pressure.

In addition to the recent increase of the Baikal Teal population in South

Korea, there has also been lately, some large and recently-unprecedented numbers

at a few sites in China.

The Baikal Teal nests in river basins in northern & northeastern Siberia. The

male is an exquisitely-patterned bird.

17 SCALY-SIDED MERGANSER

Mergus squamatus

Honshu (during 2 FONT winter tours)

This Scaly-sided Merganser has a small and declining population. Its total population is estimated as between

3,500 and 4,500 individuals. Most breed in southeastern Siberia, in Khabarovsk

and Primorye. The breeding

population in China (in the northeastern Manchurian region of Heilungkiang) is estimated as 200 to 250 pairs, and

it is declining.

So, the Scaly-sided Merganser is a rare bird. And, overall, little is known

about it. The species is closely related to both the Common Merganser (or

Goosander) and the Red-breasted Merganser, with Its range overlapping with both

even during the breeding season.

The distribution within the nesting range is sparse, along fast-flowing rivers.

Territorial pairs occupy at least 4-kilometer stretches of rivers. Birds are

normally found in pairs, or in small family parties. If in groups, outside the

breeding season, the groups are small. The birds are shy and wary. Their flight

is fast and low.

Nests are in holes of old riverside trees. After nesting, the extent of

migration is uncertain. Some birds seem to go only to the lower reaches of the

rivers along which they bred (particularly those that flow from the eastern side

of the Sikote range in Siberia). Others have been recorded considerably further

away. There are old records of wintering birds in southwestern China. Also, the

bird has been recorded elsewhere in China (particularly in the valley of the

Yangtze), and in Korea, and more rarely in Japan, northern Vietnam, and northern

Myanmar (formerly Burma).

Outside the breeding season, the Scaly-sided Merganser can be encountered on

open lakes, but generally its preference is to be along rivers.

During the winter, the species is apparently rare, but regular, in Japan. It was

first discovered there in the mid-1980's. Also during that decade, the species

was found for the first time in Taiwan in winter.

Determining the population of this species has been difficult due to the

remoteness of the breeding range and the secretiveness of the bird. Surveys

conducted in Siberia, however, seem to have shown a considerable decrease since

the 1960's.

18 STELLER'S EIDER

Polysticta stelleri

An immature Steller's Eider

photographed during a FONT tour

19 LONG-TAILED DUCK

Clangula hyemalis

Hokkaido (during

FONT winter tours)

The Long-tailed Duck has recently been

classified as a "vulnerable" species by Birdlife International.

A male Long-tailed Duck

(photo by Howard Eskin)

20 SHORT-TAILED ALBATROSS

(has also been called STELLER'S ALBATROSS)

(JPeb)

Phoebastria albatrus

pelagically, off Honshu

(during FONT spring &

winter tours twice, both times in 2000 - in January & in early

June)

The Short-tailed Albatross has a very small population, and a breeding range limited to 2

Japanese islands. Recent conservation efforts have resulted in a gradual

population increase.

But it is one of the rarest of the world's albatrosses, having recently flirted

with extinction. It was formerly abundant in the North Pacific, and seen even as

far away from the breeding sites in Japan as off the California coast of western

North America.

The global population of the Short-tailed Albatross, or the "Aho-dori"

as it is called in Japanese, following the 2006-2007 breeding season was

said to be 2,364 individuals, with 1,922 birds at the principal breeding colony

on Torishima Island, and 442 birds at the other more-southerly Japanese breeding

colony in the Senkaku Islands.

In 1954, there were only 25 birds (including at least 6 pairs) at

Torishima. In 2006, there were 426 breeding pairs on that

island.

Historical information follows below relating to the albatross colonies

at both Torishima and in the Senkakus.

The recent population figure given above was based upon the direct observation

of breeding pairs at Torishima, along with estimates of non-breeding birds at

sea and estimates of the breeding and non-breeding birds from the Senkakus

(Minami-kojima).

With that population figure noted here, the likely number of mature birds

is somewhere from 1,500 to 1,700 individuals.

Short-tailed Albatrosses have been seen during 2 pelagic ferry trips (as part

of FONT Japan Tours) off the east coast of Honshu, once in January and once in

early June.

Although the range of the bird in the Pacific is large, it seems that the Short-tailed

Albatross is most apt to be seen in areas of upwelling along the shelf

waters of the Pacific Rim, particularly along the coasts of Japan, eastern

Russia, the Aleutians and elsewhere in Alaska.

During the breeding season (at Torishima), from December to May,

the Short-tailed Albatross is in its highest density around Japan.

Satellite tracking has shown that during the post-breeding period,

females spend more time offshore from Japan and Russia, while males and

juveniles spend more time around the Aleutian Islands, the Bering Sea, and

off the coast of North America.

Juveniles have been shown to travel about twice the distance per day and spend

more time within the continental shelf than

adults.

An adult Short-tailed Albatross

(photo courtesy of Cameron Rutt)

The Short-tailed Albatross has

historically bred

on at least 11 small Japanese islands (in the Bonin, Izu, and Ryukyu (Nansei

Shoto) groups).

Away from its breeding sites, the bird has had on the open

ocean,

a

widespread range, as noted above, from Japan east to the Bering Sea and the west coast of North

America. Most of the records off Alaska, Canada, and the west coast of the

mainland US have been during June-November. The species was formerly common

along the western North American coast.

The Short-tailed Albatross was brought to the verge of extinction during the

late 19th and early 20th Centuries by plume hunters. The feathers were used for

stuffing quilts and pillows.

Another factor in the decline was habitat

disturbance on islands where the birds bred, particularly on Torishima (one of

the Izu Islands, 580 kilometers south of Tokyo). For years, it was only on the

volcanic ash slopes of that island that the species was known to breed.

Torishima was settled by humans in 1887. Until about 1900, from 10 to 50 people

lived there. The tame albatrosses were easily killed, as many as 100 to 200 a

day, up to 5 million birds in 12 years. In 1902, a major volcanic eruption on

the island killed many of the human inhabitants. The albatross population was

severely reduced, primarily by the slaughter of the birds, and secondarily by

the volcanic activity. In 1929, only about 2.000 birds remained on Torishima.

People who then recolonized the island conducted what would be the last great

massacre of the bird (nearly the entire remaining population of the species). By

1934, the Short-tailed Albatross was thought to be extinct.

An immature Short-tailed Albatross

(photo courtesy by Cameron Rutt)

Miraculously, in the early 1950's, 8 to 10 albatrosses appeared on Torishima.

As immature birds, over the years, they had been wandering the seas. During that

decade, numbers varied from 20 to 30.

In 1958, on Torishima, there were only 14

or 15 adults, 5 to 7 immatures, and 8 chicks.

Since then, there's been a slow

but steady increase in the population of the bird, with Torishima, most of the

time, the only known breeding location for the species in the world.

In 1960, all of the chicks (6 of them) were found killed. Only 22 adult birds

were found. But during the 1960's, the population began to rise more substantially to

over 50 birds.

In the 1970's it was to over 60. By 1979, the count was 95 birds

(& 22 chicks).

In March 1981, there were about 130 birds (& 34 chicks).

In November 1981, 63 eggs were found. In March 1982, there 21 chicks with about

140 adults and subadults.

The total population figures following 1979 were based

on observations at Torishima together with estimates of non-breeders away from

the colony. Thus, in 1982, the world population of the species was said to be

about 250 birds. Since 1979, over 50 eggs have been laid annually.

In 1991, the Short-tailed Albatross population had risen to about 500 birds. Since then it has

increased further. The rate of increase has been about 7% per year. Thus, the

population doubled in 10 years. Breeding success improved with grass transplantation to

stabilize nesting areas. Still, however, the population remained rather

vulnerable due to the volcanic nature of Torishima.

In 2008, ten Short-tailed Albatross chicks were moved by helicopter from

Torishima to another island, Mukojima, about 350 kilometers to the southeast in

the western Pacific Ocean.

Mukojima, in the Bonin Island group, was a site of a former

Short-tailed Albatross colony. Birds bred there until the 1920s. Mukojima is

non-volcanic.

At Torishima, 80 to 85 per cent of the world population of the Short-tailed

Albatross nest on a highly erodible slope on an outwash plain from the

caldera of an active volcano.

Monsoons send torrents of ash-laden water down the slope across the colony site.

A volcanic eruption would be catastrophic for the

birds.

During recent years, the Short-tailed Albatross has also been at a Japanese

island other than Torishima.

The bird has been on the southerly island of Minami-kojima,

one of the Senkaku Islands..

12 adult birds were found there in 1971. Breeding

was not confirmed there until 1988.

A population of 75 birds was estimated there

in 1991 (among them 15 breeding pairs). Since then, about 100 birds have been at

the island.

During late 2012, the uninhabited Senkaku Islands

were in the news due to tension between Japan and China. In Chinese, they are

the Diaoyu Islands. Translated into English,

they are the Pinnacle Islands.

They are located 200 nautical miles east of the mainland of China, 200 nautical

miles southwest of the Japanese island of Okinawa, and about 120 nautical miles

northeast of Taiwan.

The Senkaku Islands are uninhabited

by people, but they are now inhabited by birds, the rare Short-tailed

Albatrosses.

The story, told above, of the decimation of the albatrosses

at Torishima is well known. The story at the Senkaku Islands was, historically,

and unfortunately, a similar sad one, of decline and disappearance, and then,

later, recovery.

But the number of birds now at the Senkakus is not as large as at Torishima.

At the Senkakus, the albatrosses were also

slaughtered for feathers.

In 1884, it was said that "the Senkakus were so awash with albatrosses

that there was almost no room to set foot ashore".

In 1985, after victory in the Sino-Japanese War, Japan officially claimed

sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands.

That same year, the Japanese government allowed a man named Tatsushiro Koga to

"develop" the island and for he and his men to collect feathers of the

"Aho-dori",

the Short-tailed Albatross.

In 1897, they killed 160,000 of the birds, dramatically slashing the population.

In 1900, on the Senkakus, only a small number of Short-tailed

Albatrosses could be found, containing, in all, just

20 to 30 birds.

In the years that followed, with the birds gone, the business on the island

changed for a while to guano mining, and then to tuna fishing in nearby waters.

By 1940, people had left the islands, and not a single albatross

was to be found there. As late as 1963, searches there found none.

In the late 1960s, the possibility of oil and natural gas reserves under the

seabed around the Senkaku Islands was announced, and shortly after that the

issue of territorial rights for the area between Japan, China, and Taiwan began,

and, still, as of now, has continued.

But during the second half of the 20th Century, the population of the Short-tailed

Albatross has been recovering. And now it is

again a breeding bird in the Senkaku

Islands, particularly on the one island there known as Minami kojima.

Also notable on the Senkaku Islands, on Uotsuri-jima, an

endemic mammal has been found, the Senkaku Mole, Mogera

uchidai.

Regarding the history of the Short-tailed Albatross in

Japan, it should be noted that:

In 1958, the Japanese government declared the bird to be "a

special bird of protection".

In 1962, the bird became a "special national monument".

In 1993, with the ""Act for the Conservation of Endangered Species of

Wild Fauna and Flora"", the Aho-dori,

or Short-tailed Albatross

was designated by Japan as one of the "national rare species of

wild animals", and therefore always to be

protected.

Regarding the history of the Senkaku Islands, it might also be noted that:

From 1945 to 1972, the United States administered the islands before returning

them to Japanese control under the Okinawa Reversion Treaty between the US and

Japan.

In the central Pacific, at Midway Atoll (in Hawaii), 1 or 2 Short-tailed

Albatrosses were present during the last 2 decades of the 20th Century. An

incubating bird was found there in 1993, but the egg was abandoned.

More recently, in this century, a pair of Short-tailed Albatrosses came

to Midway in 2007.

In 2009, they built a nest but no egg was seen.

In November 2010, however, an egg was discovered under the presumed male of the

pair. It hatched on January 14, 2011. According to the US Fish & Wildlife

Service, the fledged youngster left the island on June 11, 2011, surviving the

tsunami which followed the Japanese earthquake of March 2011. Assumedly, that

young albatross would not return to Midway for 4 to 6 years.

That 2011 Midway fledgling represents the first time that the Short-tailed

Albatross has been known to breed outside Japanese

territory.

Back in Japan, at the Torishima breeding colony, adult birds return in October. Eggs

are laid October-November. Young are fledged from May onwards.

The following text is from "The Birds of Japan: Their Status &

Distribution", by Oliver L. Austin Jr. & Nagahisa Kuroda, published in

1953, and written when the Short-tailed (or Steller's) Albatross was thought to

be extinct:

Diomedeidae

Diomedea albatrus (Pallas)

Steller's (Short-tailed) Albatross

Japanese name: Ahodori (meaning "fool bird")

This magnificent albatross is probably extinct. Its disappearance was caused

partly by the volcanic eruptions which destroyed its former nesting grounds on

Torishima, but primarily by the activities of the plume hunters of the late 19th

and the early 20th centuries. The most-recent definite record is the one for the

few birds banded on Torishima in 1933 and killed there in 1934 (cf. Austin

1949b: 283-295).

It formerly bred on Torishima in the southern Izu Islands, on the northernmost

of the Bonin Islands, and on isolated islets in the southern Ryukyus and the

Pescadores. Its nesting season was from November through April. After the young

were on the wing, the birds moved northward along the Japanese coast to summer

in the Bering Sea, and then down the west coast of North America as far as Baja

California, before returning to their breeding grounds in late autumn. The

spring flight past Japan was marked by the numbers of dark-colored immature

birds it contained, which could be confused with the Black-footed Albatross. The

immature Steller's differed from the adult Black-footed only by its larger size

and its lighter-colored bill, neither of which could be discerned at a far

distance. An adult Steller's could also be difficult, at a distance, to tell in

the field from the adult Laysan Albatross.

21 BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS

Phoebastria nigripes

pelagically, off Honshu (during FONT spring & winter tours)

Breeds on the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (USA) and 3 outlying islands of

Japan. Colonies have disappeared on other Pacific islands. There was a near 20%

decline between 1995 & 2000.

22 BULLER'S SHEARWATER

Puffinus bulleri

pelagically, off Honshu (during FONT

spring tours)

23 CHINESE

(or SWINHOE'S) EGRET

Egretta eulophotes

Honshu (during a FONT spring tour)

Hegura Island (during a FONT spring tour)

The Chinese, or Swinhoe's Egret breeds on small islands off the coasts of

eastern Russia, North & South Korea, and mainland China. It formerly bred in

Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The global population of the Egretta eulophotes has been estimated to number

from 2,600 to 3,400 individuals.

A recent survey (published in 2012) of a breeding population on an offshore

island in southern China indicated a decline of 22 per cent in 6 years.

Overall, for the species, a decline of up to 20 per cent has been suspected over

10 years.

A Chinese, or Swinhoe's Egret was seen on a small island off the west coast of

Honshu during a FONT Japan Tour.

That small island, called Hegura-jima, is renowned

for its migration of birds, including vagrants, in the spring and fall.

More surprisingly, another Chinese Egret was found during that same FONT tour on

mainland Japan, at a rice paddy in western Honshu.

For more about birds found during the 7 FONT birding tours on that small

island off the west coast of Japan:, go to:

BIRDS OF HEGURA ISLAND, A LIST WITH SOME

PHOTOS

24 STELLER'S SEA EAGLE

Haliacetus pelagicus

Hokkaido

(during all FONT winter tours on Hokkaido)

Honshu

(during FONT winter tours on Honshu twice, a

rarity there;

apparently one bird two consecutive years)

The total population of the Steller's Sea Eagle is estimated at about 5,000 birds and declining. Most

(more than half) of those birds winter in Hokkaido, Japan, and on the nearby

Kuril Islands.

Some birds, normally in the hundreds, winter further north on the Kamchatka

Peninsula and by the Sea of Okhotsk. Breeding is exclusively in southeastern

Siberia.

27 HOODED CRANE

Grus monarcha

Kyushu

(during FONT winter tours)

The Hooded Crane breeds in wetlands in 2 areas of central Siberia. A very few have

been known, since 1991, to breed in China.

It winters at a few localities in Japan, Korea, and eastern China.

The total population has been estimated, during recent years, from about 10,000

to 11,800 birds, having increased due to artificial feeding in the winter

(particularly at a prime wintering site, Arasaki, on the southern Japanese

island of Kyushu).

More than 80% of the world's Hooded Cranes spend the winter

at Arasaki.

In 1987, the count of Hooded Cranes at Arasaki was 6,848.

In 1992, nearly 9,000 birds were there.

On November 24, 2007, the count of Hooded Cranes at Arasaki was

10,973.

There is only 1 other

wintering locality in Japan: on the main island of Honshu, at Yashiro, with

about 100 birds there.

In Japan (& Korea), the species winters almost exclusively at feeding

stations and nearby agricultural fields.

The population of Hooded Cranes has fluctuated considerably since the 1920's. At

present, the number is probably as large as at any time since then.

Hooded

Crane in

Kyushu,

(photographed during a FONT Japan Tour)

28 SWINHOE'S

(or

ASIAN YELLOW)

RAIL

32 SAUNDER'S GULL

Saundersilarus

34 FAIRY PITTA

Pitta nympha

Kyushu (during FONT spring tours)

36 IZU THRUSH (JPe)

Turdus celaenops

The Izu Thrush breeds only on the Izu Islands, in the Pacific Ocean

far offshore from Honshu, south of Tokyo. It is a winter visitor to the island

of Oshima, and it has been found to be a rare winter visitor to southern

Honshu.

37 IJIMA'S (LEAF-) WARBLER (JPe)

Phylioscopus ijimae

The Ijima's Warbler breeds on the Izu Islands, southeast

of mainland Japan, between Oshima and Aogashima, where it is present from April

to September.

Migrants occur on Honshu and Kyushu, but the species has only rarely been

encountered away from its breeding area.

It has a small and fragmented population, and is

declining.

38 BONIN WHITE-EYE (or

BONIN HONEYEATER) (JPe)

Apalapteron

(formerly

Zosterops)

familare

The Bonin White-eye, or Bonin

Honeyeater is an attractive little bird restricted only to the Ogasawara

Islands, in the Pacific Ocean, offshore from Honshu, south of Tokyo.

Since it was described by an ornithologist named Kittlitz in 1831, there have

been two known subspecies, one of which is now presumed extinct, the nominate A.

f. familare. It was on the islands of Mukojima and Chichijima.

The remaining subspecies, Apalapteron familare

hahasima survives only on Haha

Island.

A bird named after Kittlitz, is one of three species of the Ogasawara Islands,

also described in the mid 1800s, that are now extinct: the Kittlitz's Thrush,

Bonin Woodpigeon, and Bonin Grosbeak.

For an itinerary of an upcoming FONT tour

for the Bonin White-eye, or Honeyeater, and other special birds, go to:

A JAPAN TOUR IN THE SPRING FOR SOME

SPECIAL BIRDS

39 MARSH GRASSBIRD

(or

"JAPANESE MARSH WARBLER")

Megalurus p. pryeri

Honshu (during FONT spring

tours)

The Marsh Grassbird is known to breed at 6 locations on the

main Japanese island of Honshu. It probably also breeds in Heilongjiang and

Liaoning in China and at Lake Khanka in Siberia.

It is said to winter in

southern Japan, and in the Yangtze basin in China. The population in Japan is

estimated to be about 1,000 birds.

40 YELLOW

(or

"SIEBOLD'S")

BUNTING

Emberiza sulphurata

Honshu,

including Hegura Island (during FONT spring

tours)

Okinawa (during 1 FONT winter tour)

The Yellow Bunting breeds only in Japan. It is thought to

winter mainly in the Philippines, although may winter in far-southern Japan (Nansei

Shoto) and in Taiwan. It is generally uncommon in its restricted breeding range

in Japan, and it believed to have declined significantly in the 20th Century.

Species in Japan classified as NEAR-THREATENED:

41 COPPER PHEASANT (JPe)

Syrmaticus soemmerringi

Honshu (during

FONT spring & winter

tours)

Kyushu (during FONT spring & winter tours)

The Copper Pheasant is found on the Japanese islands of Honshu,

Shikoku, and Kyushu, in coniferous, broadleaved, and mixed forests. There are 6

subspecies. It was once quite common, but has declined substantially (due to,

among other things, hunting), and is now considered uncommon and difficult to

find.

Copper Pheasant,

found during FONT Japanese birding tours,

in the spring & winter on Honshu and Kyushu.

42 FALCATED DUCK

Anas falcata

Hokkaido

(during FONT winter tours)

Honshu (during FONT spring & winter tours)

Kyushu (during FONT winter tours)

A Falcated Duck photographed during a FONT tour in

Japan

43 FERRUGINOUS DUCK (also called

the FERRUGINOUS, or WHITE-EYED POCHARD)

Aythya nyroca

The range and status of the Ferruginous Duck may fluctuate

considerably from year to year, and particularly so in Asia. Thus, it can be

difficult to correctly estimate the global population or the trends for the

species.

There have marked decline of the Ferruginous Duck recently in Europe, of

more than 20 per cent in 8 countries, but the evidence of decline in the larger

Asian population is not clear.

So, the species is currently listed as being in the

"near-threatened" category. Evidence of a further, or a rapid

decline in Asia would qualify it for uplisting to "vulnerable".

The Ferruginous Duck is a vagrant in the winter in Japan.

44 LAYSAN ALBATROSS

Phoebastria immutabilis

pelagically, off Honshu (during

FONT pelagic ferry trips in spring & winter tours)

Laysan Albatross

(photo by Cameron Rutt)

45 SWINHOE'S STORM PETREL

Oceanodroma monorhis

pelagically, off the Nansei Shoto

islands of southern Japan (during a FONT pelagic ferry trip in the

spring)

46 WHITE-TAILED EAGLE

Haliaetus albicilla

Hokkaido (FONT

spring & winter

tours)

Honshu (during FONT winter tours)

The White-tailed Eagle occurs from Greenland &

Iceland east across Eurasia to eastern Siberia and Japan. The population has

been estimated as between 5,000 and 7,000 pairs, but the size of the Russian

population is poorly known.

In the western portion of the range, in Europe,

during the 19th Century and the first half of the 20th Century, numbers declined

dramatically.

An adult

White-tailed Eagle in Hokkaido

(photographed during a FONT Japan Tour)

47 ASIAN DOWITCHER

Limnodromus semipalmatus

The Asian Dowitcher is a rare breeder locally in Mongolia,

northeastern China, and nearby Russia. It is a rare migrant in

Japan.

48 BLACK WOOD PIGEON

Columba j. janthina

Honshu (on Hegura

Island) (during FONT spring tours)

Amami (during FONT spring & winter tours)

Okinawa (during FONT spring & winter tours)

The Black Wood Pigeon is an uncommon, local, and declining resident

in Japan, occurring on small islands off southern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu,

and south through the Nansei Shoto islands to the Yaeyama islands. Also in

Japan, it occurs south through the Izu Islands to the Ogasawara and Iwo Islands.

Outside Japan, it occurs locally on small islands off the south coast of South

Korea (birds seen during FONT tours on Hegura Island in the Sea of Japan, in the spring,

were probably of that population).

The species inhabits dense subtropical

forest and warm temperate evergreen broadleaf forest, with a strong dependency

on mature forest. It has declined in Okinawa during and since the 1980's due to

forestry activities. The subspecies C. j. nitens (which formerly occurred on the

Ogasawara and Iwo Islands) is now thought to be extinct.

49 LONG-BILLED MURRELET ______

Brachyramphus perdix

Hokkaido (during

FONT winter tours)

pelagically off Honshu (during a FONT winter tour)

50 RYUKYU GREEN PIGEON

(JPe)

Treron (formerly

Sphenurus)

riukiuensis

When it was considered conspecific with what is now the

Taiwan Green Pigeon, it was called the

Whistling Green Pigeon. when it also was rather inappropriately called

the

Red-capped Green Pigeon.

Amami, Okinawa (during FONT spring & winter tours)

The Ryukyu Green Pigeon is considered a

small-island specialist. It nests only on the Nansei Shoto islands of

Japan.

A Ryukyu Green Pigeon on the island of Amami

(photographed during a FONT Japan Tour)

OTHER SPECIES OCCURRING IN JAPAN THAT HAVE BEEN CONSIDERED

NEAR-THREATENED:

55 MANDARIN DUCK

Aix galericulata

Hokkaido (during

FONT spring tours)

Honshu (during FONT spring & winter

tours)

Kyushu (during FONT winter tours)

Okinawa (during 1 FONT winter tour)

A pair of Mandarin Ducks photographed during a FONT tour in Japan

(photo by Bill Leaning)

THE FOLLOWING IS PART OF A NARRATIVE RELATING TO THE

FONT TOUR IN KYUSHU, JAPAN IN JANUARY 2008,

written by Armas Hill, leader of the tour.

On the southernmost Japanese island that we visited, Kyushu,

there was the other notable species of waterfowl of our tour. Along a

particular river there, we saw, and yes - we enjoyed seeing, the Mandarin

Ducks.

Adjectives already used in this narrative, relating to waterfowl, can be used

again pertaining to the Mandarin: "brilliantly beautiful; boldly and

colorfully patterned; and exquisite".

"Mandarin", itself, is from the Sanskrit word

"mantrin", meaning "counselor".

In the mid-1500's, that word was applied to Chinese officials, as a term used by

foreigners to describe the handsomely attired senior officers of the Chinese

government.

The duck, itself, is truly of the "Far East". Its native range

is only in easternmost Asia: in not just China, but further north, breeding in

the Russian Ussurland and Kuril Islands, and in northern Japan.

The Mandarin Duck has been known as the "pearl of

Manchuria". In Russia, it's known as "Manadarinka".

It's called "Yuen Yang" in

Chinese, while in Japanese it's called "Oshidori".

In Japanese art, as early as the 8th Century, the Mandarins were

depicted, as they have been since on screen paintings, showing faithful males

and females together.

While the Japanese, or Red-crowned, Crane in Japan symbolizes

happiness and longevity, the Mandarin in Japan represents the enduring

qualities of loyalty and fidelity. The Mandarin drake and hen have been believed

to be strongly monogamous.

In China, nowadays, very few Mandarin

Ducks are to be found in the winter. But, that's not the case in southern

Japan, and particularly on Kyushu.

A few years ago I found that during the winter along the particular river,

referred to above, in southeastern Kyushu, there were a least a couple

thousand Mandarin Ducks, along the upper reaches of that river in the

wooded hills. The species was the prevalent, and, at some places, the only

species of duck along that stretch of the river. And I found that those Mandarin

Ducks were about as "wild" as ducks could be. The small groups of

ducks, along that river, would immediately fly away, as people got out of a

vehicle, on the road at a long distance from the ducks that were either swimming

on the river or tucked on and under the branches by its edge. It happened every

time, and the birds give would their distinctive calls as they flew.

These were not birds such as those in city parks. We used to visit the Mejii

Shrine in Tokyo to see the Mandarins there at a pond in

the park.

But seeing the "wilder Mandarins", in large numbers, along the

Kyushu river, has been so much more of an

experience.

Those ducks in Kyushu may come each winter from the wilder areas of mainland

Asia - in Ussurland, or from those northerly Kuril Islands. Or, maybe, they come

from northern Japan. Wherever, they come from, there are many.

A census of Mandarin Ducks wintering in Japan in 1992 tallied a total of

about 20,000 birds. The figures from that annual census in 1995 give the number

of wintering Mandarins in the Miyazaki Prefecture of Kyushu as 796 birds.

The Kyushu river we've visited for the Mandarins is in that Miyazaki

Prefecture. (A Japanese prefecture is rather like a US state.)

But the 800 or so birds just given for the entire prefecture must be a low

figure, as along that one river, during one afternoon, during one of our winter

tours in the mid-2000s, we counted at least as many as 2,000 Mandarin Ducks

- and that was without doing, in any way, what would be a proper census.

It was wonderful to see Mandarin Ducks, along that Kyushu river, again,

during our January 2008 tour!

We didn't tally as many as 2,000, but we saw quite a few. Due to some

construction along the riverside road, that would have caused us a significant

delay, we didn't go as far upriver as we normally have.

56 LONG-BILLED PLOVER

Charadrius placidus

Honshu (during

FONT

spring & winter tours)

Kyushu

(during FONT spring & winter tours)

Amami

(during FONT winter tours)

57 GREY-HEADED LAPWING

Vanellus cinereus

Honshu

(during FONT spring & winter tours)

Kyushu (during FONT winter tours)

Okinawa

(during FONT winter tours)

58 RYUKYU

ROBIN

Erithacus komadori

Amami (during FONT spring & winter tours)

Okinawa (during FONT

spring & winter tours)

The Ryukyu Robin is endemic to the Nansei Shoto islands of southern

Japan. There are two subspecies:

E. k. komadori nests on the northern

Ryukyu Islands and winters to the southern Ryukyus.

E. k. namiyei is thought to be a

resident on Okinawa.

Some birds from the central Nansei Shoto apparently migrate as far north as

southern Kyushu, with others as far south as the Yaeyama Islands (closer to

Taiwan than to Okinawa).

0

0

59 RED-BILLED

"Threatened Birds of the World" (a Birdlife International publication), Lynx Edicions, 2000, and additional information since then on the internet.