E-mail: font@focusonnature.com

Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555

or 302/529-1876

Website: www.focusonnature.com

|

PO Box 9021,

Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: font@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 or 302/529-1876 Website: www.focusonnature.com |

Rare and Threatened

Birds

in

North America

and in

Middle America

including the United States, Canada, Mexico,

and Middle America south to Panama

Noting those found

during Focus On Nature Tours

Links:

Upcoming FONT

Birding & Nature Tours in: North America

Mexico

& Central America

FONT Past

Tour Highlights

Lists & Photo

Galleries of Birds of:

North America Mexico

Central America

More Rare Birds, in: the

Caribbean Brazil

South America in the Andes & Patagonia

Japan

![]()

In the following list, places (states, provinces, or countries) where birds have been seen during FONT tours are noted.

SPECIES OF NORTH & MIDDLE

AMERICAN BIRDS

Species classified as CRITICALLY THREATENED:

California

Condor Spoon-billed Sandpiper Kittlitz's

Murrelet Cozumel Thrasher

Species classified as ENDANGERED:

Horned Guan

Gunnison

Sage Grouse Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross Black-browed

Albatross

Bermuda

Petrel Black-capped Petrel Ashy Storm Petrel Whooping Crane

Thick-billed

Parrot

Red-crowned Amazon Mangrove Hummingbird

Yellow-billed Cotinga

Bare-necked Umbrellabird

Bahama Swallow Golden-cheeked

Warbler Black-cheeked

Ant Tanager Azure-rumped

Tanager

Worthen's Sparrow

Species classified as VULNERABLE:

Highland Guan

Great Curassow Bearded Wood Partridge Greater

Prairie Chicken

Lesser Prairie Chicken Steller's Eider (& Spectacled Eider) Long-tailed

Duck Shy Albatross

Wandering Albatross Black-footed Albatross Short-tailed Albatross Trindade Petrel

Hawaiian Petrel Cook's Petrel

Stejneger's Petrel Pink-footed Shearwater Buller's Shearwater

Agami Heron Steller's Sea Eagle

Bristle-thighed Curlew Eastern

Curlew Great Knot

Red-legged

Kittiwake Marbled Murrelet Scripps's Murrelet Guadalupe Murrelet

Craveri's Murrelet

Ruddy Pigeon Great Green Macaw Red-fronted

Parrotlet Yellow-naped Amazon

Bearded Screech Owl Glow-throated

Hummingbird Red-cockaded Woodpecker Turquoise Cotinga

Three-wattled Bellbird Black-capped Vireo

Florida Scrub Jay Island Scrub Jay Pinyon Jay

Dwarf Jay White-throated Jay Sinaloa Martin

Bicknell's

Thrush Bendire's Thrasher

Sprague's Pipit Cerulean Warbler

Pink-headed Warbler Rusty Blackbird

Salt Marsh Sparrow

Species classified as NEAR-THREATENED:

Great Tinamou

Black Guan Northern Bobwhite Ocellated

Quail Marbled Wood Quail

Black-breasted Wood Quail Ocellated Turkey

Greater Sage Grouse Emperor Goose

Falcated Duck Murphy's Petrel Mottled

Petrel Fea's Petrel Cape Verde Shearwater

Sooty Shearwater Black-vented Shearwater

Fasciated Tiger Heron Orange-breasted Falcon

Plumbeous Hawk Ferruginous Hawk Montane

Solitary Eagle Crested Eagle Harpy Eagle

Ornate Hawk-Eagle Black Rail Corn Crake Piping Plover

Mountain Plover Long-billed Curlew

Black-tailed Godwit (& Hudsonian Godwit) Buff-breasted

Sandpiper Heermann's Gull

Elegant Tern Long-billed Murrelet White-crowned

Pigeon Spotted Owl

Mexican Sheartail

Resplendent Quetzal Eared Quetzal Baird's

Trogon Red-headed

Woodpecker

Gray-headed Piprites Bell's Vireo Tufted

Jay Olive-sided Flycatcher Ochraceous

Pewee

Pileated Flycatcher Belted Flycatcher Yucatan Wren Black Catbird Cassin's Finch

Golden-winged Warbler Kirtland's Warbler

Bachman's Sparrow Henslow's Sparrow

Chestnut-collared Longspur McKay's Bunting

Blue-and-gold Tanager Painted Bunting

Species that are either now EXTINCT or assumed to be:

Labrador Duck Atitlan Grebe

Eskimo Curlew

Greak Auk

Passenger Pigeon

Carolina Parakeet Imperial Woodpecker Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Bachman's Warbler

SOME SUBSPECIES OF NORTH & MIDDLE AMERICAN BIRDS

Subspecies classified as ENDANGERED:

Cozumel Curassow Masked Bobwhite

Red Knot Eastern Loggerhead Shrike

![]()

Species in North & Middle

America classified as CRITICALLY THREATENED

1 CALIFORNIA

CONDOR

______ Arizona, California

Gymnogyps californianus

The California Condor goes back a long way in California, to the Pleistocene

epoch (approximately 1.8 million to 10,000 years ago).

Among the fauna at the Rancho la Brea tarpits, of the Pleistocene,

in southern California, the California Condor seems to be the only

bird surviving today.

Some say that those "California Condors", many years ago, were

a different species, Gymnogyps amplus,

a larger version of the present-day bird.

Gymnogyps amplus was described in

1911 from Upper Pleisocene bones from the Samwel Cave in California.

It was said to be slightly larger and more robust than Gymnogyps

californianus, and a direct ancestor of it.

Today, the California Condor has a wingspan of over 9 feet and a weight

of up to 23 pounds, making it one of the largest birds in the world.

The transition from G. amplus to G.

californianus is thought to have taken place around the very end

of the Pleistocene, borne out by the difficulty had by paleontologists

determining the species at that time.

Gymnogyps

bones

have been found in at least 25 places in the United States and

Mexico.

In Arizona, at the Grand Canyon, where free-flying California

Condors can again be seen now, fossil history dates back to the late Pleistocene.

Condors first appeared in the Grand Canyon fossil record more than

43,000 years ago. A perfectly intact condor skull from the late

Pleistocene epoch has been found in the Stevens Cave in the Grand Canyon

National Park. Radiocarbon has shown that skull to be 12,000 years old.

During the Pleistocene, the range of the California Condor formed a large

u-shaped swath across North America from British Colombia south

through Oregon and California to Baja California in Mexico

and then east through Texas and across to Florida.

The condor bones that have been discovered in Florida are

seemingly the earliest known, from the Reddick beds, dating back to the Middle

Pleistocene and around 200,000 years ago, and from the Pamlico formation of

the early Upper Pleistocene going back over 100,000 years. Apparently, no

later condor bones from Florida have been found.

The California Condor was described to science in 1798, by the English

naturalist George Shaw, who saw the bird along the coast of California.

One of the more famous early sightings of the California Condor was

during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, when one was seen feeding on dead

fish near the mouth of the Columbia River, in Sprague, Washington

State, in November 1805.

Following a second condor found during the expedition, Captain Meriwether Lewis

wrote nearly 3 pages in his journal in relation to the bird. He speculated that

it was "the largest bird of North America ... it weighed 25 pounds

... (and) between the extremities of the wings, it measured 9 feet 2

inches."

By the 1940s,

the range of the California Condor did not extend beyond southern

California.

In Arizona, where as noted condors can be seen today, they

lived, as they had for many years, until the early 1920s.

By 1982, only 22 free-ranging California Condors remained in California.

The upper photograph below was taken of one of those birds in late

1981.

By 1986, only 1 female and 4 male condors roamed free. The U.S. Fish &

Wildlife Service sanctioned capturing those birds and adding them to the captive

breeding population. The last one was captured in April 1987,

In 1992, 63 condors existed in captivity. A few were released

that year into the wild. 8 young birds were returned to California, but within a

couple years, half had perished from collisions with power lines, shooting, or

poisoning.

In the fall of 1996, 6 young condors were taken to a holding pen atop Vermilion

Cliffs near Page, Arizona. After several weeks of feeding them stillborn calf

carcasses, they were released.

From their release site, they wandered through the Monument Valley and Grand

Canyon in northern Arizona, Bryce Canyon in Utah, Mesa Verde in Colorado, and as

far north as Flaming Gorge in southwestern Wyoming.

Condor releases have continued about annually in northern Arizona.

In 2003, the Arizona condor population produced its first wild

offspring in the Grand Canyon. A number of the birds, in that area, during the

summer of 2006 traveled north to Utah to reside in hills near Zion National

Park, but in the winter they returned to Arizona, where food was always

available for them..

By March 2009, the number of wild-living condors in Arizona and southern

Utah reached 75. In May of that year, the Peregrine Fund reported on its website

that there were 358 California Condors. 189 of them were wild birds in

California, Arizona, and elsewhere in the US, and in Baja California in Mexico.

169 of them were in captivity, including those in zoos, maintained for breeding

purposes, or pending release.

Until recently, in Mexico, the California Condor has been

classified as extirpated. In Canada, where the bird occurred in southern

British Columbia, it was extirpated about two centuries ago.

The above photograph,

taken in California in 1981,

is of one of the last California Condors in the wild.

(photo by Armas Hill)

A California Condor &

Northern Raven photographed in September 2009 in Arizona

(photo by Doris Potter)

2 SPOON-BILLED

SANDPIPER ______ (an Asian bird,

has occurred very rarely in Alaska & western Canada)

Eurynorhynchus pygmeus

Described by Linnaeus back in 1758, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper

is now an overall

very rare species, breeding in far eastern Siberia. It winters coastally in

Southeast Asia.

In North America, it has occurred very rarely in western and northern Alaska.

Further south, in British Columbia, Canada, there was a record of a

breeding-plumaged adult near Vancouver from July 30 to August 3, 1978.

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was seen during one

FONT Winter Japan Tour on the southern Japanese island of Amami.

The global population of the species was, not long ago, in the early 2000s,

estimated as under 4,000 birds. The population at the known breeding grounds was

said to be about 1,000 individuals, thus indicating a greater than 50 per

recent reduction in the last decade or so.

Not only is the global population of the species declining rapidly, there is

another problem: in that population, recently, there has been very little

recruitment of young birds.

Although breeding success is low, it seems that the main factor in the

Spoon-billed Sandpiper's decline appears to be the low rate of return to the

breeding grounds.

Data collected from 2003 to 2009 on birds at Meinypilgyno (the main breeding

site for the species in far-eastern, Siberian Russia), it is suggested that

recruitment into the adult breeding population was effectively zero in

all those years (2003 to 2009), except for 2005 & 2007.

When we first started at FONT to note the classification of the Spoon-billed

Sandpiper in the 1990s it was listed as "vulnerable".

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was uplisted to the category of "critically

endangered" in 2008, when the total breeding population of the species

was thought to be from 150 to 320 pairs.

In 2009-2010, the estimate was sadly revised downward to from 120 to 200 pairs.

One factor that may be responsible for the decline of the Spoon-billed

Sandpiper has been the loss of resting and feeding areas along the migration

flyway for the bird. There are about 8,000 kilometers of coastline between the

bird's breeding grounds in Arctic Russia and its non-breeding grounds in

southeast Asia. That's a long distance traveled by the bird that's about 6

inches in length.

The particular site along the coast in South Korea where the largest-ever

concentration of migrating Spoon-billed Sandpipers was recorded is now

the site of the world's biggest reclamation project. That habitat, vital for

bird, has been lost.

Other tidal mudflats around the coast of the Yellow Sea are rapidly being lost

to agriculture, industry, and urban development.

Another factor in the bird's decline is that at its wintering grounds in Myanmar

(Burma) and Bangladesh, numbers of them have fallen victim to the trapping of

sandpipers by hunters.

And when a population is as small as it for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper,

any number lost by such practice is detrimental.

Starting in 2008, an international team of researchers has surveyed, each year

in January, in Myanmar the Arakan coast and that of the Gulf of Martaban, the

wintering population of Spoon-billed Sandpipers.

The coast of the Gulf of Martaban has become known as the most important

wintering site for the species with about 220 birds found in 2010/2011.

Based on data from the breeding grounds, that is about half the estimated world

population, and over twice as many birds as found at all the other known

wintering sites put together.

Although the trapping by local hunters in Myanmar, referred to above, does not

deliberately target Spoon-billed Sandpipers, they are caught as a "bycatch"

in nets set for larger birds or pegged close to the mud to catch retreating fish

as the tide goes out.

The 2010 survey confirmed this large-scale hunting and trapping along the

Gulf of Martaban. Hunters indicated trapping up to 350 waders (or shorebirds) in

a single night.

One morning in January 2010, a hunter brought the survey team a Spoon-billed

Sandpiper he had caught the previous night along with about 100 Red-necked

Stints.

The single Spoon-billed Sandpiper, still alive, was marked with a red

flag and released by a group of local children.

That same hunter also indicated that he had last caught a Spoon-billed

Sandpiper the previous August (in 2009). It was an immature bird.

Not only are young birds more likely than adults to fall victim to hunters, they

are also likely to be affected disproportionately because they are thought not

to return to the breeding grounds until they are two years old. Some, during

that time, are speculated to spend the entire intervening year in their

non-breeding area.

In September 2012, at a global meeting in Korea of biologists and other

environmental scientists, a list was distributed of the "100 Most

Endangered Species in the World", referring to all life, animal and plant.

It was under the auspices of the International Union for Conservation of Nature,

and the Zoological Society of London.

In that list, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper was positioned as number #10, making it

the "most endangered bird species on Earth" in the opinion of that

group, and sadly a candidate, unless something is done, for extinction.

For more about the 100 Species in the List, go to: ENDANGERED

SPECIES

Above: a

Spoon-billed Sandpiper in breeding plumage.

Below: In non-breeding plumage.

In 2012, the conservation group SOS, "Save Our

Species" was a partner in an innovative project to

boost the number of juvenile Spoon-billed Sandpipers at their breeding grounds

in Chukotka, in eastern Russia.

With the WWT, the "Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust", a IUCN

member working with the Moscow Zoo and "Birds Russia",

there was tremendous success, during the summer of that year, hatching, rearing,

and releasing 9 Spoon-billed Sandpiper chicks.

Those 9 chicks were hatched from 11 eggs carefully taken from the breeding

grounds on the tundra. They were monitored, hatched, and nourished in the nearby

village of Meinypil'gyno before being released. The project required constant

attention and effort. The fledglings gained strength living in an open-air

aviary designed to shelter the birds from predators. For added protection, a

guard kept vigil day and night.

The pioneering work is significant in that in the wild just 3 Spoon-billed

Sandpipers out of every 20 eggs survive long enough to start their 8,000

kilometer migration to southeast Asia.

Also, as part of the project, another 20 thumbnail-sixed eggs were transported

from Arctic Russia to a WWT facility in Slimbridge, England.

The first chicks were hatched there on July 4, 2012.

Of the 20 eggs that were brought to the UK, 18 chicks successfully hatched.

Those new birds were added to 12 fully-grown Spoon-billed Sandpipers that were

already at the WWT center, having been brought in at the start of the

conservation breeding program in November 2011.

The eggs, that were brought to England in 2012, were for more than 17 hours in

flight, transported by helicopter and airplane in a journey that took, totally,

7 days to complete.

One of the eggs cracked during an airport inspection and had to be sealed using

nail varnish.

When the Spoon-billed Sandpiper chicks hatched, they were about the size of a

large bumblebee.

The WWT hopes that the increasing size of the captive flock of Spoon-billed

Sandpipers in the UK would help trigger breeding behavior in the birds when they

would later reach maturity at two years of age.

A Spoon-billed Sandpiper

illustrated in England

in the early 20th Century,

about a hundred years

before a conservation project in the UK

aiming to save the species.

3 KITTLITZ'S

MURRELET ______ Alaska

Brachyramphus brevirostris

According to Birdlife International, the Kittlitz's Murrelet

has recently been suffering "an extremely rapid population decline".

The species occurs in Alaska and eastern Russia. About 70 per cent

of its total population is in Alaska, from Cape Lisburne south to the

Aleutian Islands and east to LeConte Bay.

The Alaskan population of the Kittlitz's Murrelet is said to have

fallen to as low as about 8,000 birds, with surveys indicating that the number

may have declined by 80 to 90 per cent during the 15 years from 1993

to 2008.

For an upcoming FONT tour to an area with the critically endangered Kittlitz's

Murrelet: ALASKA TOUR

4 COZUMEL THRASHER ______ Mexico

(endemic to Cozumel Island)

Toxostoma guttatum

In the past, the Cozumel Thrasher was fairly common on the Mexican

island of Cozumel, off the northeastern coast of the Yucatan

Peninsula, the only place where the bird occurs (or possibly,

occurred).

If it still exists, the Cozumel Thrasher is very rare, with a tiny

population, assumed to be less than 50 individuals.

The Cozumel Thrasher became so rare immediately after Hurricane

Gilbert in September 1988. After that, there were only a few

sightings, with even less after Hurricane Roxanne in 1995.

During surveys looking for the Cozumel Thrasher in 2004, there

were 4 observations (that may have been of the same individual).

But there was another sighting observation that same year at a different site.

There was another possible sighting in 2006.

In Mexico, the Cozumel Thrasher is classified as an endangered

species.

For a List of Birds of Cozumel Island, noting those that have been seen

during FONT tours, and including both some other bird species as well as

subspecies endemic to the island: COZUMEL

BIRDS

Cozumel Thrasher

Species in North &

Middle America classified as ENDANGERED:

5 HORNED

GUAN ______

Guatemala,

Mexico

Oreophasis derbianus

The Horned Guan lives on volcanic "islands

in the sky", occurring only on a few volcanoes in western Guatemala

and nearby Chiapas in Mexico. On those mountains, it resides in broadleaf

evergreen forest higher than 6,000 feet above sea level.

The first specimen of the beautiful, and yet odd, Horned Guan was

obtained in the mid-1800s by the collector J. Quinones, supplying birds

to the English aviculturist and amateur zoologist Lord Derby. It was his name of

that English lord that was incorporated into the bird's scientific name, Oreophasis

derbianus, done so by G.R. Gray in 1844.

That first specimen was said to have come from mountain named Volcan de Fuego

in Guatemala.

And it was on that mountain where the Horned Guan was first observed

"in the field" by the English ornithologist Osbert Salvin in 1861.

Over the years, very few other scientists ever saw, let alone studied, the rare

bird.

In a book published in 1969, it was said that altogether only 13 scientists had

ever seen Oreophasis derbianus since

it was discovered.

Even to this day, not many people have actually seen the Horned Guan.

Apparently, throughout the entire 20th Century, the rare Horned Guan was never

seen on Volcan de Fuego, but small numbers were found to exist on

other high mountains mostly near Lake Atitlsn but also locally elsewhere in

Guatemala.

Among those "other high mountains" is the Volcan Toliman, where the

bird has been seen by FONT tour

participants.

The global population of the Horned Guan was

estimated to be less than 1,000 birds in the 1970s. It is said to have declined

since then.

In Mexico, the Horned Guan is classified as an endangered

species.

Below, there is a narrative describing an exciting encounter, during a FONT

tour, with rare Horned Guans where they live only in remote pristine mountain

forests.

Above: a photo of 1 of 2

Horned Guans

seen during the FONT Guatemala tour in July 2007

(photo during the tour by Josue de Leon, one of our guides)

Below: a captive Horned Guan at a zoo in Guatemala

THE FOLLOWING IS PART OF A NARRATIVE RELATING TO THE FONT TOUR IN GUATEMALA IN

JULY 2007,

DESCRIBING A HIKE ON A MOUNTAIN DURING WHICH WE SAW THE RARE HORNED GUAN,

AND TWO OTHER

BIRDS IN THIS LIST, THE AZURE-RUMPED TANAGER and the HIGHLAND GUAN,

written by Armas Hill, leader of the tour:

Extraordinary, for sure, during our FONT July '07 Guatemala

tour, was July 17th.

That was the day when we looked up into the green-leaved canopy of the mountain forest

above us, and saw one of the most spectacular of birds, the Horned Guan!

We had started that day early - very early in fact. We were driven, when it was

still dark, by one of our two guides on the mountain, up to the dirt road until

it ended. Beyond that point, it was a trail that continued to go up - and

up.

The area where we were is truly a wonderful piece of Guatemalan countryside.

The forest on the slopes of the volcanic mountain is pristine.

During one of our previous Guatemala tours in that area where the dirt road

ends, we saw, during a morning, 3 species of Hawk-Eagles fly overhead:

the Black, the Black-and-white, and the Ornate. That alone

says that the area is good for birds, with forest pristine indeed.

During our July '07 tour, as we arrived at the end of the road, it was earlier

in the morning than during our previous visits.

As noted, it was still dark.

Actually, there was well over an hour to go before the first light of dawn.

We looked upward to a brilliant array of stars, in a very clear sky, far away

from any city lights.

The "W" of Cassiopeia was bright, and

with it, a background of many stars.

The Milky Way, spread across the

sky, was brilliant. In the distance, we heard the call of a Mottled Owl.

We had just seen a Pauraque along the road.

Shortly after we started out on the upward trail, still in darkness, the second

of our two guides pointed to a hole and a mound of loose dirt on the trail. This

was the guide who lives on the mountain, and, we were told, "never left

it".

And, we were told that he knows, better than anyone, the haunts and

the habits of the rare and the (sorry to repeat myself) spectacular Horned

Guan.

Anyway, the hole and the mound on the trail, he told us, was the workings of a Puma.

"When it does poo", he said, "the animal covers it up". Yes,

the area where we were was pristine, and wild!

As we walked, when still dark, we flushed a bird from its nest in an arcing

branch by the trail. We soon began to hear some birds, as we experienced a

wonderful dawn chorus - one quite different than what we would hear otherwise,

nearly anywhere else.

The first sound we heard was the beautiful song of the Spotted

Nightingale-Thrush.

A short while later, in the distance, we heard the

call-note of the Spotted Wood Quail.

It's funny how the two birds named

"spotted" never were - by us. We only heard them.

We did both hear and see, that day, the Ruddy-capped Nightingale-Thrush.

It too has a beautiful song, as its name implies.

Motmots call early, as they contribute to the dawn chorus. As we walked,

still and ever upward, we heard both the Blue-crowned Motmot (that

occurs in various habitats throughout Guatemala), and the Blue-throated

Motmot (that's only in the high mountains).

There was a nice assortment of Wrens that we heard at dawn, and that we

later saw during daylight:

the Plain, the Gray-breasted Wood, the Spot-breasted, the

Rufous-browed, and the Rufous-and-white.

Among other birds that we saw and heard in the forest that morning was a Mockingbird,

called the Blue-and-white.

In addition to the Nightingale-Thrushes, others in that tribe that we

encountered that morning were the White-throated Thrush and Brown-backed

Solitaire.

The Rufous-browed Peppershrike was vocal, as it tends to be. We also saw

a couple of its cousins that day, the Chestnut-sided Shrike-Vireo, and

then later, in an area of forest on a lower slope, the Green Shrike-Vireo was

present. It, too, was vocal.

In the higher forest, as we still continued upward to where we aimed to see the Horned

Guan, we came across a couple brown birds of the forest, the Ruddy

Foliage-gleaner, close to the ground, and the Scaly-throated

Foliage-gleaner, higher in a tree. Neither stayed in view for long. Nor did

the Black-throated Jay, also up in a tree. Staying around a bit longer

were some Emerald Toucanets.

The Yellowish Flycatcher, an empidonax, was easy to see along our

trail, as were some other birds that we encountered as they encountered some

ants on

which to feed.

The most-common bird in that flock, drawn to the ants was the aptly-named Common

Bush Tanager.

But their supporting cast was pretty good, including the Golden-browed

Warbler (a beauty), the Slate-throated Whitestart (also

dapper, with whatever name - it has been called the Slate-throated

Redstart), and the Tawny-throated Leaftosser, the Rufous-browed

Wren, and the Chestnut-capped Brush Finch.

Also close to us, as we stopped one time for a rest, a brilliant male Violet

Sabrewing, a large hummingbird (yes, very violet), sat on a low tree branch.

A little further away, in the trees, a colorful little bird, good to see, was

the Blue-crowned Chlorophonia.

Larger, and also colorful, was the Collared Trogon we saw well.

Also with bright red coloration, was the male White-winged Tanager that

we observed in the trees.

All of these birds were, of course, very nice, but we still had not seen THE

guan. We had yet seen a guan of any kind. The Highland Guan also

occurs.

The Horned Guan is not the only avian rarity that lives on the Guatemalan

mountain we visited that day. There's another. It's a gem called the Azure-rumped

Tanager.

For years, through most of the 20th Century, there were only just a

few records of the bird. It has a limited range, at only a particular elevation,

on the Pacific slope of a handful of mountains in southern Mexico and

northwestern Guatemala.

There are not many of them.

But, luckily, we did encounter the rare species early in the morning, during our

hike on the mountain. A pair had just recently bred in the area. After nesting,

these tanagers travel about with other small forest birds in a group.

The Azure-rumped Tanager was just said to be a gem. And that it is. The

bird is a mix of various blue colorations. One of those hues, the one in the

bird's name, azure, is the color of the rump. The bird's crown is mauve. The

bluish back is mottled with black and has a green tint. The underparts are a

pale blue. The wings have turquoise.

Something else, very blue - a bright blue, was seen during our hike along the

trail. On the ground, we did not know what they were at first. But, actually,

they were bird droppings.

The little pieces were as brilliantly colored as the

Blue Morpho butterflies that fly in the tropics. The guide, who had

earlier told about the puma, said that the little bright blue pieces were

droppings from the bird that we sought, the Horned Guan!

A couple hours after we saw those droppings on the trail, and after we had

started our downward trek, the guides asked us, again, as they had a few times

earlier, to stay still on the trail, and they wandered off into the forest.

Yes, they had done that a few times. But this time, the man who's never left the

mountain, signaled to all of us to follow him into a part of the forest. We did so,

and then looked up, as directed, into the trees branches.

At first, IT was rather obscured by leaves, but then we could see the form of a

large turkey-like bird. Yes, it was the Horned Guan!

Actually, there were two of them there.

And, as the birds moved gently and

quietly along the branches, we had wonderful looks, first by eye, then in our

binoculars, and then in a telescope.

There wasn't a feature of the bird that we didn't see from the beak to the

tail-tip, including the long red horn, the light-colored eye with a black

eyespot, the pink legs, the white breast, and the bluish-black back.

The birds were both generally silent. One did emit a call, once, as it flew a

short distance from one tree to another.

The Horned Guan is very rare. Its total population may not be much more

than a thousand individuals, if that.

Like the Azure-crowned Tanager, it

has a very limited range on only a handful of volcanic mountains in southern

Mexico and in northwestern Guatemala.

After our extraordinary moments with the Horned Guans, we resumed our

walk along the trail down the slope of the mountain. Before too long, we came

across yet another guan.

This time, it was the other guan species in the area, the Highland Guan,

mostly black, with a bright red throat wattle and legs. So, we were 2 for 2 with

the species of guan on that part of the mountain.

During a previous tour, on a lower portion of that same mountain, we had seen Crested

Guans.

There was something else bright blue that we found on the trail as we

descended the mountain that afternoon on July 17, 2007.

Fruits, they were, the size and same shape as olives. The guide, who lives on the

mountain, told us they were the favored food of the Horned Guan.

He called

it "acetuna", which is the Spanish

word for "olive". But they were

not green or black. Rather, they were as a bright a blue as the Horned Guan

droppings we had seen earlier that day on the trail. Their color, really, was

the same.

The same color as that of the small fruits and guan droppings was also in the

plumage of

another bird that we saw on that Guatemalan mountain that day - the blue in the Long-tailed

Manakin (below).

6

GUNNISON SAGE GROUSE

______ Colorado

Centrocercus minimus

The Gunnison Sage Grouse is

a recently-described species (in 2001) of the USA heartland. It is very localized with a

range restricted to southwest Colorado and southeast Utah. It is thought to have

formerly been more widespread (possibly in New Mexico, eastern Arizona,

southwest Kansas, and Oklahoma).

Now the bird occurs in 6 or 7 counties of southwest Colorado and a single county

in adjacent southeast Utah.

The entire population is estimated at being less

than 5,000 birds, with most (2,500-3,000) in the Gunnison Basin (of Colorado).

Elsewhere populations number less than 300, with fewer than 150 in Utah.

It has disappeared from several population pockets since 1980, with an overall

decline of over 60% in males attending breeding leks in the Gunnison Basin in

the last 50 years.

Formerly considered a subspecies of the more-northerly Sage Grouse (now Greater

Sage-Grouse), Gunnison Sage-Grouse of both sexes have plumages

similar to that species, but are about 30% smaller.

7 ATLANTIC

YELLOW-NOSED ALBATROSS ______

(a rarity in eastern North America, offshore &

onshore)

Thalassarche chlororhynchos

8 BLACK-BROWED ALBATROSS ______ (a

rarity in eastern North America, offshore)

Thalassarche melanophris

Nearly 75% of the world population

of the Black-browed Albatross breed on the Falkland Islands in the South

Atlantic Ocean.

The species also nests on South Georgia Island and on outer islands of southern

Chile: Diego Raimirez, Idlefonso, Evout and Diego de Almagro.

The Black-browed Albatross is now classified as endangered, as the species has undergone a

significant population

decline due at least in part to long-line fisheries.

A Black-browed Albatross

photographed during a FONT tour

(photo by Alan Brady)

9 BERMUDA

PETREL (or Cahow) ______

(a rarity in

eastern North America, offshore)

Pterodroma cahow

10 BLACK-CAPPED PETREL ______ North

Carolina, offshore

Pterodroma hasitata

The Black-capped Petrel has a very small, fragmented, and declining breeding

range that is only on some Caribbean islands.

It is now known to nest in Haiti and the adjacent Dominican Republic, where

there are an estimated 1,000 breeding pairs, mostly on the Massifs de la Selle

and de la Hotte in southern Haiti.

In the Dominican Republic, where nesting occurs in the Sierra de Baoruco (Baoruco

Mountains), nests are in cliffs only at a high altitude of almost 7,000 feet

above sea level.

In the Lesser Antilles, small numbers have recently been recorded on Dominica,

and over nearby offshore waters, suggesting that the species may nest on that

island.

The bird is now believed to be extinct on Guadeloupe, where it was common in the

19th Century. It may have bred, in the past, on Martinque.

Even during the breeding season, the Black-capped Petrel is highly pelagic,

occurring at that time as far from Caribbean islands as in the area of the Gulf

Stream off North Carolina, USA. Birds disperse over the Caribbean Sea and

Atlantic Ocean from that area (off North Carolina) to waters off northeast

Brazil, but the at-sea range is said to have recently

contracted.

As noted, nests are in burrows in cliffs, in montane forest, at about 1,500 to

2,300 meters (4,500 to nearly 7,000 feet) above sea level. Nesting is colonial,

and begins in December.

As also noted, birds often commute long distances between breeding sites in the

mountains and foraging sites at sea. When doing so, the Black-capped Petrel is

primarily nocturnal and crepuscular. It feeds on fish, invertebrate swarms,

fauna associated with Sargassum seaweed, and squid. Birds are attracted to

localized upwellings, where the mixing of oceanic waters produces patches of the

sea that are rich in nutrients.

A single Black-capped Petrel was seen during the first FONT Caribbean pelagic

trip, on February 8,

1996, off the west coast of Puerto Rico. The sighting was late in the

day.

And Black-capped Petrels were seen during nearly every FONT pelagic trip off

the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

A Black-capped Petrel

photographed during a FONT pelagic trip

11 ASHY STORM PETREL ______

California, offshore

Oceanodroma homochroa

The global breeding population of the Ashy

Storm Petrel is essentially confined to offshore California islands: the

Farallons (75 per cent of the population) and the Channel Islands (the rest),

where there are very limited breeding opportunities in rocky crevices.

Most of these storm petrels flock together in Monterey Bay in the fall,

potentially exposing the entire population to any single, possible calamity.

And of course the concentrated breeding colonies also face threats such as nest

disturbance by humans and livestock, and predation by introduced mammals such as

rats and cats, and depredation by gulls. These are threats to many of

California's seabirds, but the Ashy Storm Petrel, being so local and

geographically isolated, is especially susceptible.

In Mexican waters, the Ashy Storm Petrel has been classified as a threatened

species.

12 WHOOPING

CRANE

______ Nebraska,

Texas

Grus americana

During a FONT tour in March 2014,

Whooping Cranes were seen nicely at the Aransas National Wildlife

Refuge in Texas.

Back in the early 1990s, on one occasion, a single Whooping Crane

was seen with Sandhill Cranes during a FONT tour in the spring in Nebraska,

where many Sandhill Cranes stage along the Platte River during their

northward migration.

A family of Whooping Cranes at

the Aransas Refuge,

with the young bird flanked by its parents.

(photo by Marc Felber)

In North America, the Whooping

Crane is the rarest crane in the world, although it is not now as rare as it once was.

Since Whooping Cranes reached their low point in 1941, with only 15

recorded in Texas after the disappearance of those that had wintered nearby on

the immense King Ranch, the wildlife services of the United States and Canada,

working together, have brought about an amazing comeback.

In 1941, that low of 15 birds was the entire population of the species in the

wild.

After a century of shooting, egg-collecting, and habitat destruction (including

the drainage of Gulf Coast marshes to create rice fields), just those very few

birds remained.

Recently,

2011 was a good year for the Whooping Crane, particularly so in

relation to the long-established population that breeds in the Northwest

Territories of Canada and winters in the Aransas area of coastal Texas.

In August of 2011, 37 Whooping Crane chicks fledged from 75

nests in the Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta, Canada.

12 juvenile Whooping Cranes were captured there in August, bringing the

total number of radioed birds to 23.

That, itself, is more than what the total Whooping Crane population was

back in the 1940s, when only from 14 to 20 birds were dutifully reported

as the number known to exist then by the Chicago Tribune.

The size of the 2010-2011 winter flock at Aransas was 283 birds.

During the winter prior to that, 2009-2010, there were 263 birds.

In 2008-2009, there were 270. In 2007-2008, 237. In 2005-2006, 220 birds.

10 captive-raised Whooping Cranes were released in February 2011 in Louisiana,

where a non-migratory flock historically resided until 1950. Seven of those

birds were alive seven months later.

Unfortunately, in 2011, no chicks were fledged in the wild,

reintroduced Whooping Crane flocks in Florida or Wisconsin.

Problems were with incubation behavior in Florida and nest abandonment in

Wisconsin.

The captive Whooping Crane flocks had good production in 2011. 17

chicks were raised in captivity for the non-migratory flock in Louisiana, and 18

were headed for Wisconsin.

Including the juvenile cranes reintroduced in the fall of 2011, flock

sizes were 278 in the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock, 115 in the

Wisconsin to Florida flock, 20 non-migratory birds in Florida,

and 24 in Louisiana.

With also 162 cranes in captivity, the total number of Whooping Cranes

at the end of 2011 was 599 birds, and that was the most in about a

century!

That number resulted from years of work, of protecting and nurturing the birds.

Going back just a few years, to the summer of 2007, a record number of

Whooping Crane chicks hatched that year at the Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada.

An aerial survey of the breeding grounds found 65 nests and 84 new

chicks. Among the chicks, there were 28 sets of twins. The previous

summer, there had been 76 new chicks, including among them 24 sets of twins.

A couple years further back, in 2005, the total Whooping Crane

population in North America was 470.

213 of those birds were in the self-sustaining flock that arrived that fall

at Aransas in Texas.

The rest were the birds that were residents in Florida, those in captivity, and

those in a flock that was re-introduced in Wisconsin and taught to migrate to

Florida.

In 2005, in the Wood Buffalo National Park, 54 nesting pairs of

Whooping Cranes fledged 40 chicks. Most of them were

old enough to fly by mid-August, enabling them to escape predators and migrate

to Texas. 33 birds of the year arrived at Aransas that winter.

And 2005 was also a good year in Texas too, as high rainfall and abundant flowing

freshwater increased the number of blue crabs, the crane's favorite food

(although they also eat snakes, snails, rats, and other creatures).

Historically, fossil records suggest that Whooping Cranes have existed

for several million years, and once lived from the prairies of Alberta, Canada

to central Mexico.

Another note from 2005: sadly 2 male Whooping Cranes were shot that year,

in November, while migrating through Kansas. They were quickly discovered on the

ground. One died within a week. The other had surgery to repair a broken wing,

and was then flown to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, where

it subsequently died due to respiratory problems related to its injuries.

With a population of just a few hundred birds, even though considerably more

than before, every bird matters.

In Canada and Mexico, the Whooping Crane is classified

as an endangered species, but it has occurred in Mexico only very

rarely.

The Whooping Crane was described to science by Linnaeus back in 1758.

An excellent book referring to cranes is entitled "The Birds of Heaven -

Travels with Cranes" by Pete Matthiessen, with paintings and drawings by

Robert Bateman.

Above: a drawing of Whooping

Cranes at Aransas in Texas,

given as a gift to Armas Hill by the illustrator, Charles Gambill

Below: 2 Whooping Cranes photographed by Howard Eskin

at the Redrock National Wildlife Refuge in Montana, USA in 1984.

Howard, who was there for fishing, was not expecting

to find these birds. It was just he and the birds

(and hopefully a few fish) along the river.

13 THICK-BILLED

PARROT ______ Mexico

(formerly

in Arizona)

Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha

In Mexico, the Thick-billed

Parrot is classified as an endangered species.

14

RED-CROWNED AMAZON ______ Texas (but

more so in Mexico)

Amazona viridigenalis

In Mexico, the Red-crowned Amazon is classified as an endangered

species.

15 MANGROVE HUMMINGBIRD ______ Costa

Rica (endemic)

Amazilia boucardi

16 YELLOW-BILLED COTINGA (or ANTONIA'S COTINGA) ______ Costa

Rica, Panama

Carpodectes antoniae

In Panama, the Yellow-billed Cotinga is classified

as a critically endangered species.

17 BARE-NECKED UMBRELLABIRD

______ Costa Rica, Panama

Cephalopterus glabricollis

In Panama, the Bare-necked Umbrellabird has been

classified as an endangered species.

18 BAHAMA SWALLOW ______ (endemic

to the Bahamas, but has strayed to Florida)

Tachycineta cyaneoviridis

19 GOLDEN-CHEEKED

WARBLER ______ Guatemala, Honduras,

Texas

Setophaga

(formerly

Dendroica)

chrysoparia

In Mexico, the Golden-cheeked Warbler is classified as a threatened

species. Overall, as placed in this list, it is globally classified by

Birdlife International as an endangered species.

The Golden-cheeked Warbler nests only in one limited region, the "Hill

Country" of Texas, making it an endemic breeder in the United States,

in Texas, and, there, just in that one region in the central part of the state.

Outside the breeding season, it is in Mexico and Central America. Mostly it is

in northern Central America. Although there have been some recent sightings in

Costa Rica and Panama, it is very rare there.

The Golden-cheeked Warbler has been seen during FONT tours in the winter in

Guatemala and Honduras, where the most have been seen in a highland forest in

eastern Honduras.

In the US, the Golden-cheeked Warbler has been seen and heard during FONT tours

in Texas in the area of the "Hill Country" and the Edwards Plateau,

from March to May.

The bird is best located, initially, by its voice in the canopy. That is how we

found it during our March 2014 FONT Texas Tour in the Lost Maples Natural Area,

when we first heard it, and then saw it on March 11, the day of its first

sighting of the season there, as it arrived on its nesting territory.

The Golden-cheeked Warbler nests, locally, in mature juniper and oak

woodlands.

20 BLACK-CHEEKED

ANT-TANAGER ______ Costa Rica

(endemic)

Habia atrimaxillamis

21 AZURE-RUMPED

TANAGER (or CABANIS' TANAGER) ______ Guatemala,

Mexico

Tangara cabanisi

The Azure-rumped Tanager has a very small geographical range, only

occurring locally in evergreen broadleaf mountain forest in Chiapas, Mexico

and western Guatemala, generally between 1200 and 1500 meters above sea

level. It has also been found in clearings with second-growth fruiting

scrubs.

Until the 1970s, there were only 3 records of the

species:

the type specimen in western Guatemala near Quetzaltenango from which the

bird was described in 1868,

another specimen, an immature female, taken in 1937 on the mountain

Ovando in Chiapas, Mexico

and another near Cacahoatan in Chiapas in 1943.

Between 1972 & 1977, there were sightings in the area of El Triunfo,

in Chiapas, Mexico.

In the 1980s,

the Azure-rumped Tanager was found on the slope of Sierra Madre de

Chiapas in Mexico, and at a couple locations in western Guatemala.

During FONT tours in Guatemala, the Azure-rumped Tanager has been found a few

places in the western part of the country, including the Pacific slope near

Quetzaltenango (apparently near where the type specimen as taken over a

hundred years previously), and on the slope of a volcano near Lake

Atitlan near where the rare Horned Guan occurs.

The AZURE-RUMPED TANAGER is referred to in a narrative

earlier in this list, relating to the HORNED GUAN (number

#5 in the

list).

In Mexico, the Azure-rumped Tanager has been classified as

an endangered species.

The Cabanis', or Azure-rumped,

Tanager

22 WORTHEN'S SPARROW

______ Mexico (endemic)

Spizella atrogularis

The Worthen's Sparrow is now an endemic Mexican species. Only included in this North America list, as

the type specimen for the species was collected at Silver City, New Mexico in

June 1884. That bird was probably part of a small resident population that was

subsequently extirpated.

The species is now classified by Birdlife International

as endangered. It has been classified as critically endangered.

In Mexico, the Worthen's Sparrow is classified as an endangered

species.

23 HIGHLAND GUAN ______ Guatemala,

Honduras

Penelopina nigra

In Mexico, the Highland Guan is classified as a threatened

species.

The HIGHLAND GUAN is referred to in the narrative

earlier in this list, relating to

the HORNED GUAN.

24 GREAT CURASSOW ______ Costa

Rica, Guatemala, Panama

Crax rubra

In Mexico, the Great Curassow is classified as a

threatened species. In Panama, it is classified as

vulnerable.

Note below in Subspecies Section regarding Crax

rubra griscomi on Cozumel Island, Mexico.

25 BEARDED WOOD PARTRIDGE

______ Mexico (endemic)

Dendrortyx barbatus

In Mexico, the Bearded Partridge is classified as an endangered

species.

26 GREATER PRAIRIE CHICKEN

______ Colorado, Nebraska

Tympanuchus cupido

There have historically been 3 subspecies of Greater

Prairie Chickens.

In the eastern United States, the subspecies T.c. cupido,

called the "Heath Hen", occurred formerly in bushy habitat from

Boston south to Washington. It was extirpated on the mainland about 1835. It

continued to survive beyond that on the Massachusetts offshore island of

Martha's Vineyard until it was last reported there in 1932. At that time, the

eastern race of the Greater Prairie Chicken became extinct.

Another race of the species, in coastal Texas, is now very rare. T.c.

attwateri, the "Attwater's Prairie Chicken" has

declined in 30 years from 8,700 individuals in 1937 to 1,070 in 1967. After

another 30 years, in 1998, only 56 individuals remained in 3 isolated

populations. Even with released captive-reared birds, that subspecies is

severely threatened.

The most wide-ranging of the Greater Prairie Chicken subspecies (and the

one occurring in eastern Colorado and Nebraska), T.c. pinnatus,

has declined over much of its range. The population in the late 1970's was

estimated as 500,000. Due to its being in small isolated populations, the

species overall is at considerable risk.

In Canada, the Greater Prairie Chicken has been extirpated.

Above &

below: Greater

Prairie Chickens

photographed during FONT tours in Colorado.

Below: at their lek at dawn,

photographed during the FONT tour in April 2009.

27 LESSER PRAIRIE CHICKEN ______

Colorado, Kansas

Tympanuchus pallidicinctus

The Lesser Prairie Chicken has declined

substantially since the European settlement of the Great Plains. That decline is

thought to be over 90% since the 19th Century, and nearly 80% since the early

1960's.

In 1980, Lesser Prairie Chickens occupied only 8% of their original range

(which was historically throughout the southwest Great Plains, in southeast

Colorado, southwest Kansas, western Oklahoma, northern Texas, and eastern New

Mexico). Now, it is only in small, scattered populations.

The population estimate was about 50,000 birds in about 1980 (from 42,000 to

55,000 in 1979). 20 years later, in 1999, the population was estimated as 10,000

to 25,000, mostly in northwest Texas and Kansas.

A Lesser Prairie Chicken

photographed during a FONT tour in Kansas

28 STELLER'S EIDER ______ Alaska

Polysticta stelleri

In the United States, particularly Alaska, the Steller's

Eider has been classified as a threatened species by the US Fish

& Wildlife Service.

Above: a first-winter male Steller's Eider

photographed during a FONT tour

(photo by Claude Bloch)

Below: a group of Steller's Eiders, males & females,

where probably the most can be seen

anywhere in the world, in Estonia,

as during the FONT tour there in April.

The SPECTACLED EIDER, Somateria fischeri

(seen during FONT

tours in Alaska) has until recently also been classified by Birdlife

International as "vulnerable", but at least for now its status has

been changed to that of "a species of least

concern".

Spectacled Eiders form large wintering flocks in the Bering Sea.

From aerial surveys in the 1990s, the average estimate of the number of birds in

those flocks was over 300,000.

The breeding population of the Spectacled Eider in Alaska has been

classified as threatened by the US Fish & Wildlife Service.

29 LONG-TAILED DUCK ______ Alaska

Clangula hyemalis

The Long-tailed Duck has been uplisted by Birdlife

International to the "vulnerable" category due to an apparently

drastic decline in the number of wintering birds in recent years, especially in

the area of the Baltic Sea.

Since the early 1990s, the global population of the Long-tailed Duck has

undergone a rapid decline over 3 generations, since 1993.

Outside North America, the Long-tailed Duck has been seen during FONT tours

in Iceland (where they breed) and in Hokkaido, Japan (where they

winter).

A male Long-tailed Duck

(photo by Howard Eskin)

30 SHY ALBATROSS ______ (a

rarity in western North America, offshore)

Thalassarche cauta

31 WANDERING ALBATROSS

______ (a rarity in western North

America, offshore)

Diomedea exulans

32 BLACK-FOOTED

ALBATROSS ______ California, Washington

State, both offshore

Phoebastria nigripes

In Mexican waters, the Black-footed Albatross is

classified as a threatened species.

33 SHORT-TAILED

ALBATROSS ______ (a rarity in

western North America, offshore; but now less rare)

Phoebastria albatrus

The Short-tailed Albatross has a very small population, and a breeding range limited to 2 Japanese islands. Recent conservation efforts have resulted in a gradual population increase.

But it is one of the rarest of the world's

albatrosses, having recently flirted with extinction. It was formerly abundant

in the North Pacific, and seen even as far away from the breeding sites in Japan

as off the California coast of western North America.

The global population of the Short-tailed Albatross, or the "Aho-dori"

as it is called in Japanese, following the 2006-2007 breeding season was

said to be 2,364 individuals, with 1,922 birds at the principal breeding colony

on Torishima Island, and 442 birds at the other more-southerly Japanese breeding

colony in the Senkaku Islands.

In 1954, there were only 25 birds (including at least 6 pairs) at

Torishima. In 2006, there were 426 breeding pairs on that island.

Historical information follows below relating to the albatross colonies

at both Torishima and in the Senkakus.

The recent population figure given above was based upon the direct observation

of breeding pairs at Torishima, along with estimates of non-breeding birds at

sea and estimates of the breeding and non-breeding birds from the Senkakus

(Minami-kojima).

With that population figure noted here, the likely number of mature birds

is somewhere from 1,500 to 1,700 individuals.

Short-tailed Albatrosses have been seen during 2 pelagic ferry trips (as part

of FONT Japan Tours) off the east coast of Honshu, once in January and once in

early June.

Although the range of the bird in the Pacific is large, it seems that the Short-tailed

Albatross is most apt to be seen in areas of upwelling along the shelf

waters of the Pacific Rim, particularly along the coasts of Japan, eastern

Russia, the Aleutians and elsewhere in Alaska.

During the breeding season (at Torishima), from December to May,

the Short-tailed Albatross is in its highest density around Japan.

Satellite tracking has shown that during the post-breeding period,

females spend more time offshore from Japan and Russia, while males and

juveniles spend more time around the Aleutian Islands, the Bering Sea, and

off the coast of North America.

Juveniles have been shown to travel about twice the distance per day and spend

more time within the continental shelf than adults.

An adult Short-tailed Albatross

(photo by Cameron Rutt)

The Short-tailed Albatross

has historically bred on at least 11 small Japanese islands (in the Bonin, Izu,

and Ryukyu (Nansei Shoto) groups).

Away from its breeding sites, the bird has had on the open ocean, a widespread

range, as noted above, from Japan east to the Bering Sea and the west coast of

North America. Most of the records off Alaska, Canada, and the west coast of the

mainland US have been during June-November. The species was formerly common

along the western North American coast.

The Short-tailed Albatross was brought

to the verge of extinction during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries by

plume hunters. The feathers were used for stuffing quilts and pillows.

Another factor in the decline was habitat disturbance on islands where the birds

bred, particularly on Torishima (one of the Izu Islands, 580 kilometers

south of Tokyo). For years, it was only on the volcanic ash slopes of that

island that the species was known to breed.

Torishima was settled by humans in 1887. Until about 1900, from 10 to 50

people lived there. The tame albatrosses were easily killed, as many as 100 to

200 a day, up to 5 million birds in 12 years. In 1902, a major volcanic eruption

on the island killed many of the human inhabitants. The albatross population was

severely reduced, primarily by the slaughter of the birds, and secondarily by

the volcanic activity. In 1929, only about 2.000 birds remained on Torishima.

People who then recolonized the island conducted what would be the last great

massacre of the bird (nearly the entire remaining population of the species). By

1934, the Short-tailed Albatross was thought to be extinct.

An immature Short-tailed Albatross

(photo by Cameron Rutt)

Miraculously, in the early 1950's, 8 to 10

albatrosses appeared on Torishima. As immature birds, over the years,

they had been wandering the seas. During that decade, numbers varied from 20 to

30.

In 1958, on Torishima, there were only 14 or 15 adults, 5 to 7 immatures, and 8

chicks.

Since then, there's been a slow but steady increase in the population of the

bird, with Torishima, most of the time, the only known breeding location for the

species in the world.

In 1960, all of the chicks (6 of them) were found

killed. Only 22 adult birds were found. But during the 1960's, the population

began to rise more substantially to over 50 birds.

In the 1970's it was to over 60. By 1979, the count was 95 birds (& 22

chicks).

In March 1981, there were about 130 birds (& 34 chicks). In November 1981,

63 eggs were found. In March 1982, there 21 chicks with about 140 adults and

subadults.

The total population figures following 1979 were based on observations at

Torishima together with estimates of non-breeders away from the colony. Thus, in

1982, the world population of the species was said to be about 250 birds. Since

1979, over 50 eggs have been laid annually.

In 1991, the Short-tailed Albatross population

had risen to about 500 birds. Since then it has increased further. The rate of

increase has been about 7% per year. Thus, the population doubled in 10 years.

Breeding success improved with grass transplantation to stabilize nesting areas.

Still, however, the population remained rather vulnerable due to the volcanic

nature of Torishima.

In 2008, ten Short-tailed Albatross chicks were moved by helicopter from

Torishima to another island, Mukojima, about 350 kilometers to the southeast in

the western Pacific Ocean.

Mukojima, in the Bonin Island group, was a site of a former

Short-tailed Albatross colony. Birds bred there until the 1920s. Mukojima is

non-volcanic.

At Torishima, 80 to 85 per cent of the world population of the Short-tailed

Albatross nest on a highly erodible slope on an outwash plain from the

caldera of an active volcano.

Monsoons send torrents of ash-laden water down the slope across the colony site.

A volcanic eruption would be catastrophic for the birds.

During recent years, the Short-tailed Albatross

has also been at a Japanese island other

than Torishima.

The bird has been on the southerly island of Minami-kojima,

one of the Senkaku Islands..

12 adult birds were found there in 1971. Breeding was not confirmed there until

1988.

A population of 75 birds was estimated there in 1991 (among them 15 breeding

pairs). Since then, about 100 birds have been at the island.

During late 2012, the uninhabited Senkaku Islands

were in the news due to tension between Japan and China. In Chinese, they are

the Diaoyu Islands. Translated into English,

they are the Pinnacle Islands.

They are located 200 nautical miles east of the mainland of China, 200 nautical

miles southwest of the Japanese island of Okinawa, and about 120 nautical miles

northeast of Taiwan.

The Senkaku Islands are uninhabited

by people, but they are now inhabited by birds, the rare Short-tailed

Albatrosses.

The story, told above, of the decimation of the albatrosses

at Torishima is well known. The story at the Senkaku Islands was, historically,

and unfortunately, a similar sad one, of decline and disappearance, and then,

later, recovery.

But the number of birds now at the Senkakus is not as large as at Torishima.

At the Senkakus, the albatrosses were also

slaughtered for feathers.

In 1884, it was said that "the Senkakus were so awash with albatrosses

that there was almost no room to set foot ashore".

In 1985, after victory in the Sino-Japanese War, Japan officially claimed

sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands.

That same year, the Japanese government allowed a man named Tatsushiro Koga to

"develop" the island and for he and his men to collect feathers of the

"Aho-dori",

the Short-tailed Albatross.

In 1897, they killed 160,000 of the birds, dramatically slashing the population.

In 1900, on the Senkakus, only a small number of Short-tailed

Albatrosses could be found, containing, in all, just

20 to 30 birds.

In the years that followed, with the birds gone, the business on the island

changed for a while to guano mining, and then to tuna fishing in nearby waters.

By 1940, people had left the islands, and not a single albatross

was to be found there. As late as 1963, searches there found none.

In the late 1960s, the possibility of oil and natural gas reserves under the

seabed around the Senkaku Islands was announced, and shortly after that the

issue of territorial rights for the area between Japan, China, and Taiwan began,

and, still, as of now, has continued.

But during the second half of the 20th Century, the population of the Short-tailed

Albatross has been recovering. And now it is

again a breeding bird in the Senkaku

Islands, particularly on the one island there known as Minami kojima.

Also notable on the Senkaku Islands, on Uotsuri-jima, an

endemic mammal has been found, the Senkaku Mole, Mogera

uchidai.

Regarding the history of the Short-tailed Albatross in

Japan, it should be noted that:

In 1958, the Japanese government declared the bird to be "a

special bird of protection".

In 1962, the bird became a "special national monument".

In 1993, with the ""Act for the Conservation of Endangered Species of

Wild Fauna and Flora"", the Aho-dori,

or Short-tailed Albatross

was designated by Japan as one of the "national rare species of

wild animals", and therefore always to be

protected.

Regarding the history of the Senkaku Islands, it might also be noted that:

From 1945 to 1972, the United States administered the islands before returning

them to Japanese control under the Okinawa Reversion Treaty between the US and

Japan.

In the central Pacific, at Midway Atoll (in Hawaii), 1 or

2 Short-tailed Albatrosses were present

during the last 2 decades of the 20th Century. An incubating bird was found

there in 1993, but the egg was abandoned.

More recently, in this century, a pair of Short-tailed

Albatrosses came to Midway in 2007.

In 2009, they built a nest but no egg was seen.

In November 2010, however, an egg was discovered under the presumed male of the

pair. It hatched on January 14, 2011. According to the US Fish & Wildlife

Service, the fledged youngster left the island on June 11, 2011, surviving the

tsunami which followed the Japanese earthquake of March 2011. Assumedly, that

young albatross would not return to Midway for 4 to 6 years.

That 2011 Midway fledgling represents the first time that the Short-tailed

Albatross has been known to breed outside Japanese

territory.

In Canadian Pacific waters, the Short-tailed Albatross is

classified as a threatened species. In US waters, it has been classified

as an endangered species.

Back in Japan, at the Torishima breeding colony, adult birds

return in October. Eggs are laid October-November. Young are fledged from May

onwards.

The following text is from "The Birds of Japan: Their Status &

Distribution", by Oliver L. Austin Jr. & Nagahisa Kuroda, published

in 1953, and written when the Short-tailed (or Steller's) Albatross

was thought to be extinct:

Diomedeidae

Diomedea albatrus (Pallas)

Steller's (Short-tailed) Albatross

Japanese name: Ahodori (meaning "fool bird")

This magnificent albatross is probably extinct. Its disappearance was caused

partly by the volcanic eruptions which destroyed its former nesting grounds on

Torishima, but primarily by the activities of the plume hunters of the late 19th

and the early 20th centuries. The most-recent definite record is the one for the

few birds banded on Torishima in 1933 and killed there in 1934 (cf. Austin

1949b: 283-295).

It formerly bred on Torishima in the southern Izu Islands, on the northernmost

of the Bonin Islands, and on isolated islets in the southern Ryukyus and the

Pescadores. Its nesting season was from November through April. After the young

were on the wing, the birds moved northward along the Japanese coast to summer

in the Bering Sea, and then down the west coast of North America as far as Baja

California, before returning to their breeding grounds in late autumn. The

spring flight past Japan was marked by the numbers of dark-colored immature

birds it contained, which could be confused with the Black-footed Albatross.

The immature Steller's differed from the adult Black-footed only

by its larger size and its lighter-colored bill, neither of which could be

discerned at a far distance. An adult Steller's could also be difficult,

at a distance, to tell in the field from the adult Laysan Albatross.

34 TRINDADE PETREL

______

North Carolina, offshore

Pterodroma arminjoniana

35 HAWAIIAN PETREL

______ California, offshore

(a rarity)

Pterodroma sandwichensis

36 COOK'S

PETREL

______ (a rarity in western North America,

offshore)

Pterodroma cookii

37 STEJNEGER'S PETREL ______ (a

rarity in western North America, offshore)

Pterodroma longirostris

38 PINK-FOOTED SHEARWATER ______

California, Washington State, both offshore

Puffinus creatopus

In Canadian Pacific waters, the Pink-footed Shearwater is

classified as a threatened species.

39 BULLER'S SHEARWATER ______ California,

Washington State, both offshore

Puffinus bulleri

40 AGAMI HERON ______ Belize, Costa Rica, Guatemala,

Panama

Agamia agami

In Mexico, the Agami Heron has been classified as

a species of special concern.

Agami Heron

41 STELLER'S

SEA EAGLE ______ (an Asian

species, a rarity in Alaska)

Haliaeetus pelagicus

42 BRISTLE-THIGHED CURLEW ______

Alaska

Numenius tahitiensis

In 1769, the Bristle-thighed Curlew was discovered wintering on South

Pacific islands, first collected by Captain Cook's voyagers in Tahiti.

The species was described to science 20 year later.

Its nesting grounds in Alaska were not discovered until almost 180 years

later, in 1948. Just prior to that, it was the only bird species in North

America whose nesting area was still a mystery.

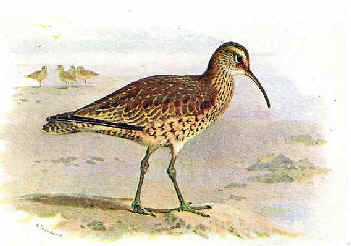

Bristle-thighed Curlew

(photo by Cameron Rutt)

43 EASTERN CURLEW ______

Alaska (an Asian species, in Alaska a

rarity)

Numenius madagascariensis

The Eastern Curlew has been called the Far Eastern

Curlew.

44 GREAT KNOT ______

(an Asian species, a rarity in Alaska)

Calidris tenuirostris

45 RED-LEGGED

KITTIWAKE ______ Alaska

Rissa brevirostris

In the mid-1970s, the total population of the

Red-legged Kittiwake was estimated at about 260,000 individuals. It declined

to about 168,000 by the mid-1990s. Most of this decline was on the Pribilof

Islands of Alaska.

46 MARBLED MURRELET ______ Alaska,

British Columbia, California, Washington State

Brachyrmphus marmoratus

At some of the above places, during FONT tours, seen both offshore and from

shore.

The Marbled Murrelet, a small

seabird, has the curious and unusual trait of nesting high in the limbs of

old-growth coniferous trees in the forest.

Its nesting habits are so unusual for a seabird that they remained a mystery

until 1974, when a nest was discovered in the Big Basin State Park, in Santa

Cruz County.

Other than a smaller population in the Santa Cruz Mountains, the entire breeding

range of the Marbled Murrelet in California is in the conifer

forests on the immediate coast of Del Norte, Humboldt, and northern Medocino

Counties.

Federally, the Marbled Murrelet is classified as THREATENED. In California,

it is classified as ENDANGERED.

In Canada, the Marbled Murrelet is classified as a threatened

species.

There is a fine book entitled "Rare Bird - Pursuing the Mystery of the

Marbled Murrelet", by Maria Mudd Ruth, published in 2005, that is an

excellent read about the bird.

47 SCRIPPS'S MURRELET ______

California, Washington State, both offshore

Synthliboramphus scrippsi

Now here's a name to try to say quickly:

"Scripps's Murrelet".

It's now the name of what was part of the Xantu's Murrelet. Now Mr.

Xantu only has a hummingbird for a namesake.

The AOU (American Ornithologists Union) split the species known as the

Xantu's Murrelet in July 2012.

The Scripps's Murrelet, Synthliboramphus scrippsi occurs

at sea mostly in California. Away from its breeding sites, it occurs north,

rarely, to northern California and more rarely to Oregon and Washington

State,

and south to southern Baja California, Mexico.

It breeds on islands off southern California: San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Anacapa,

Santa Barbara, San Clemente, and formerly Santa Catalina, and in western Baja

California, Mexico on San Benito, and Coronado and San Jeronimo islands. On

larger islands (such as San Miguel, Santa Cruz, and San Clemente), it is

confined largely or entirely to offshore rocks.

In Mexico, the Scripp's Murrelet is classified as an endangered

species.

48 GUADALUPE MURRELET ______

Synthliboramphus hypoleucus

The other half of what was the Xantu's Murrelet is now the Guadalupe

Murrelet.

Synthliboramphus hypoleucus

breeds on offshore

rocks and islands off western Baja California, Mexico from Guadalupe Island

south to the San Benito Islands. Breeding is unconfirmed on San Martin Island,

in Baja California, and San Clemente and Santa Barbara Islands in California,

USA.

It presumably winters offshore within the breeding range along the Pacific coast

of Baja California.

In Mexico, the Guadalupe Murrelet is classified as an endangered

species.

To read more about splits the last few years by the AOU and by the BOU (the

British Ornithologists Union) & others:

TAXONOMIC CHANGES

49 CRAVERI'S MURRELET ______ California,

offshore

Synthliboramphus craveri

50 RUDDY PIGEON ______ Costa Rica, Panama

Patagioenas subvinacea

In Panama, the Ruddy Pigeon has been classified as a vulnerable

species.

51 GREAT GREEN MACAW ______ Costa Rica,

Panama

Ara ambigua

In Panama, the Great Green Macaw is classified as an

endangered species.

52 RED-FRONTED PARROTLET ______ Costa Rica,

Panama

Touit costariceensis

In Panama, the Red-fronted Parrotlet has been classified as a vulnerable

species.

53 YELLOW-NAPED AMAZON ______ Costa Rica

Amazona auropalliata

54 BEARDED SCREECH OWL ______ Guatemala

Megascops barbarus

55 GLOW-THROATED HUMMINGBIRD ______

Panama

Selasphorus ardens

In Panama, the Glow-throated Hummingbird is classified

as a critically endangered species.

56 RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER ______

North Carolina

Picoides borealis

57 TURQUOISE COTINGA ______

Costa

Rica, Panama

Cotinga ridgwayi

The Turquoise Cotinga is one of the seven species of "blue

cotingas".

These include:

In Central America, the Lovely Cotinga, Cotinga

amabilis, the Turquoise (or Ridgway's) Cotinga,

Cotinga ridgwayi, and the Blue (or Natterer's)

Cotinga, Cotinga nattererii.

In South America, the Purple-breasted Cotinga, Cotinga

cotinga (the first of 3

species in the genus described by Linnaeus), Banded Cotinga, Cotinga

maculata, Plum-throated Cotinga, Cotinga

maynana, and the Spangled Cotinga, Cotinga

cayana.

Of these, the Turquoise Cotinga has one of the most restricted

ranges, occurring only in southwestern Costa Rica and Panama.

In Panama, the Turquoise Cotinga is classified as a

critically endangered species.

In 1941, when the then-young naturalist Alexander Skutch

settled at his then-new farm "Los Cosingos" in southern

Costa Rica, among the birds the he especially noted was the Turquoise

Cotinga.

He referred it as being among the "colorful species" (and that it is)

that resided there, including also the Fiery-billed Aracari, Golden-naped

Woodpecker and Orange-collared Manakin, each of these birds also with

a limited range.

Dr. Skutch lived at "Los Cosingos" for 62 years. The morning

of the day when Alexander Skutch died there, Dana Gardner, a friend and the

illustrator of many of Skutch's books, told of "a beautiful Turquoise

Cotinga that came out to sun itself in a bare tree at the edge of Skutch's

yard at Los Cosingos".

In 1969, Alexander Skutch wrote about the nest of the Turquoise

Cotinga. He wrote that it was a long-sought nest for him to find.

The slight, open structure was situated on a trifurcation of the horozontal

lowest branch of a Muneco tree, about 30 feet above a little-used path.

By standing on the top of his longest ladder and raising a mirror attached to a

long pole, Skutch saw two buffy eggs spotted all over with brown.

As she had built the nest alone, so the grayish, speckled female

incubated alone, often sitting continuously for two or more hours, and then

remaining away for from half an hour to well over an hour.

The only sound Skutch ever heard from that female bird was a low whistling of

her wings in flight.

That silence did not surprise Skutch, for he had never heard any other sound